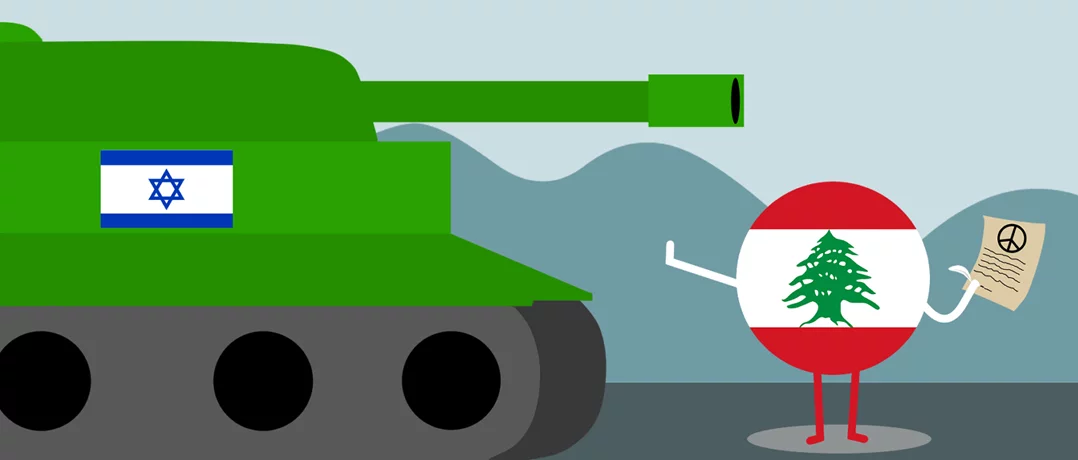

How Lebanon negotiated with restraint and authority in 1949.

A throwback to the 1949 Lebanese Israeli armistice

A throwback to the 1949 Lebanese Israeli armistice

The Lebanese Israeli Armistice: When Lebanon Still Spoke as a State

It is often claimed, whether out of ignorance or political convenience, that Lebanon never negotiated with Israel. This claim collapses under the weight of historical record. In March 1949, Lebanon signed a formal armistice agreement with Israel under United Nations supervision. This was not a marginal or forced act, nor was it a temporary improvisation forced by battlefield realities. It was a conscious decision taken by a functioning constitutional state that still understood sovereignty as responsibility, diplomacy as authority, and war as a last resort rather than a permanent condition.

Revisiting the Lebanese-Israeli Armistice is therefore not an exercise in nostalgia. It is a necessary correction to a distorted collective memory that presents Lebanon as eternally passive, structurally incapable of decision-making, or condemned to political paralysis. In 1949, Lebanon acted as a state - cautiously, legally, and deliberately. That this moment is often overlooked today reveals more about subsequent political breakdowns than about the nature of the Lebanese state at independence.

Lebanon’s calculated distance from the 1948 war

Lebanon’s participation in the 1948 Arab Israeli War was limited not by circumstance, but by deliberate political calculation. From the outset, Beirut refused to frame the conflict as an existential struggle or a civilizational battle, unlike Cairo, Damascus, or Baghdad, where the war was portrayed as a defining test of Arab destiny and regional power. For the Lebanese political class, the war was neither total nor redemptive. It was a constrained obligation arising from Arab League commitments, carefully calibrated to avoid transforming Lebanon into a permanent theater of confrontation.

This restraint was rooted in Lebanon’s demographic and constitutional realities. In 1948, Lebanon was a small, newly independent state with a fragile sectarian equilibrium institutionalized by the National Pact of 1943. The leadership understood that mass mobilization or prolonged warfare risked internal fracture before any external gain. Unlike centralized states with large populations and standing armies, Lebanon’s political order relied on balance, consensus, and institutional continuity. War, especially ideological war, threatened all three.

The recent memory of the French Mandate further reinforced this caution. Independence had been achieved through negotiation, not armed struggle. Lebanese leaders internalized the lesson that international legitimacy and legal process were more reliable guarantors of sovereignty than military adventure. This political culture shaped Beirut’s approach to the 1948 conflict and explains why Lebanon consistently resisted pressure to escalate its involvement beyond symbolic participation.

Militarily, Lebanon lacked both the manpower and the infrastructure required for sustained engagement. The Lebanese Army, formally established only in 1945, was still in its formative years. It was modest in size, lightly equipped, and designed primarily for internal security and border control rather than offensive warfare. Lebanese decision-makers were fully aware that escalation beyond limited engagement would expose the state to strategic overstretch without credible prospects of altering the regional balance of power.

This awareness translated into concrete operational choices. Lebanese military involvement remained geographically limited, avoided deep incursions, and operated under tight civilian oversight. Beirut resisted repeated calls to expand operations or subordinate Lebanese forces to broader Arab command structures. Participation was political, not maximalist. Lebanon sought to demonstrate Arab solidarity without surrendering its national calculus.

The arab military effort: Numbers without coherence

Lebanon’s restraint was further reinforced by the structural weakness and fragmentation of the Arab military effort in 1948. Far from constituting a unified or coordinated force, the Arab armies that entered Palestine were divided by competing command structures, uneven levels of training, and incompatible strategic objectives. Collectively, Arab states deployed approximately 25,000 to 30,000 troops at the outset of the war. This figure, often cited rhetorically as evidence of Arab strength, masked profound institutional dysfunction.

Egypt, the largest contributor, committed roughly 10,000 troops, many of whom were poorly trained conscripts operating under politicized command. Syria fielded fewer than 3,000 soldiers, constrained by limited logistical capacity and internal political instability. Iraq deployed approximately 3,000 troops, operating at a distance from their supply lines and largely detached from unified strategic planning. Transjordan’s Arab Legion, numbering around 4,500, stood out as the most professional force, but it pursued objectives shaped by British training and Hashemite interests rather than Arab League consensus.

Lebanon’s own contribution remained limited to a few hundred troops, a reflection not only of capacity but of political intent. Beirut recognized that integrating fully into such a fragmented coalition would not enhance Lebanon’s security. It would entangle it in rivalries, expose it to strategic miscalculations, and weaken civilian control over military decision-making.

By mid-1948, Jewish forces that would later form the Israel Defense Forces numbered between 35,000 and 40,000. More importantly, they operated under a centralized command structure, unified doctrine, and a single political authority capable of rapid decision-making. The imbalance was not merely numerical. It was institutional. Wars are not won by declarations, summits, or slogans, but by command unity, logistics, and political clarity - all of which were conspicuously absent on the Arab side.

The united nations as a shield, not a substitute

Against this backdrop, Lebanon’s turn toward the United Nations was not an abdication of sovereignty, but an assertion of it. The transition from ceasefire to armistice after 1948 was driven by UN mediation, particularly through the efforts of Dr. Ralph J. Bunche. His approach rested on a simple but firm premise: only recognized states could negotiate, enforce, and sustain agreements.

Lebanon aligned naturally with this framework. While other delegations sought to revisit battlefield outcomes, ideological claims, or symbolic victories, Beirut focused on legal clarity, border stability, and international supervision. The armistice talks were not an arena for confrontation, but a mechanism to formalize disengagement.

This choice reflected Lebanon’s belief that sovereignty was best preserved through institutions rather than improvisation. By anchoring negotiations within UN mechanisms, Lebanon protected itself from unilateral pressures and reinforced its status as a distinct political actor rather than a subordinate component of a broader ideological front.

The 1949 armistice agreement: Minimalist by design

The Lebanese Israeli Armistice Agreement was signed on 23 March 1949. The negotiations took place at Rosh Hanikra (Ras El-Nakoura) in the customs office at the Lebanon-Palestine border. The agreement was signed on behalf of Israel by Lieutenant-Colonel Mordechai Makleff, Yehoshua Pelman and Shabtai Rosenne, Legal Advisor at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On behalf of the Government of Lebanon the Agreement was signed by Lt. Colonel Toufic Salem and Major Joseph Harb.

The Armistice Agreement reaffirmed the international boundary inherited from the Mandate period and established UN-supervised mechanisms to prevent escalation. It deliberately avoided political normalization, diplomatic symbolism, or expansive security commitments.

This restraint was not accidental. Lebanon sought security without alignment and disengagement without entanglement. The armistice was not a peace treaty and did not claim to resolve the broader Arab–Israeli conflict. It was a legal instrument designed to restore predictability along a vulnerable frontier while preserving Lebanon’s diplomatic autonomy.

In choosing minimalism, Lebanon demonstrated strategic discipline. The agreement reflected a clear understanding of what the state could enforce and what it could not.

The army and the logic of the state

The armistice framework assumed the existence of a national army capable of respecting ceasefire obligations and cooperating with international observers. In 1949, this assumption was broadly accepted. The Lebanese Armed Forces were perceived as a state institution rather than a factional or ideological actor.

The agreement embedded military restraint within a legal and international framework. Force was subordinated to order. Authority flowed from institutions, not mobilization. This conception aligned with Lebanon’s early post-independence understanding of the army as a guarantor of internal stability rather than an instrument of regional confrontation.

Conclusion: A political instinct worth remembering

The Lebanese Israeli Armistice of 1949 represents a moment when Lebanon still possessed strategic self-awareness. It chose institutions over improvisation, diplomacy over militarization, and limits over illusions.

This was not weakness. It was political maturity. Lebanon negotiated not because it was incapable of war, but because it understood what war would cost and what it could not sustain.

Remembering this moment is not about reviving old agreements or reopening closed files. It is about reclaiming a forgotten truth: Lebanon once knew how to act, decide, and speak as a state.

Shuster, Rhoda. “Ralph J. Bunche - United Nations Mediator.” Negro History Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 8 (May 1956), pp. 174–176, 180.

United Nations. Armistice Agreements between Israel and the Arab States (1949).

Hughes, Matthew. Lebanon’s Armed Forces and the Arab–Israeli Conflict. (2005).

Arab League. Proceedings and Resolutions of the Arab League Council, 1947–1949.

Morris, Benny. 1948: A History of the First Arab–Israeli War. Yale University Press, 2008.

United Nations Security Council. Reports of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (UNTSO), 1948–1949.