Lebanon has a rich historic tradition for attracting British

intelligence agents.

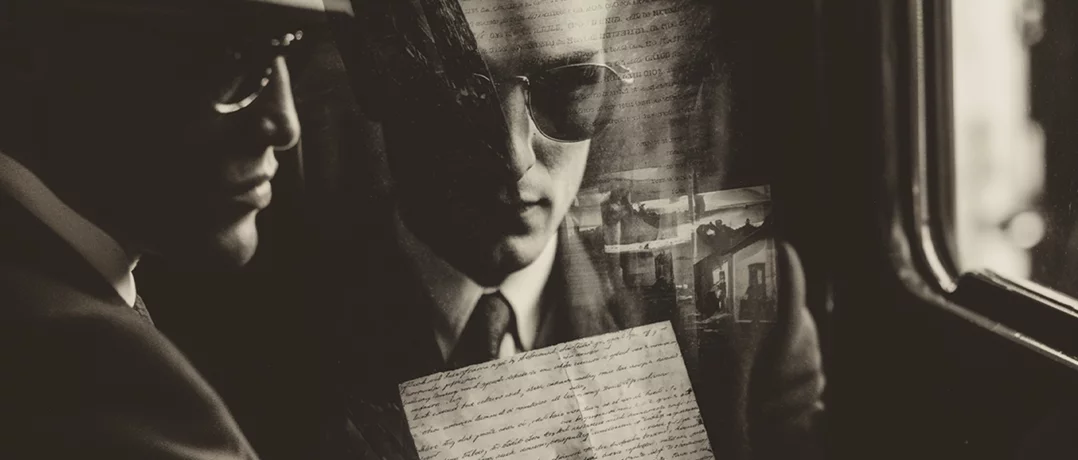

A trail of spies

A trail of spies

On

Monday, the Chouf Cedar Reserve dedicated a 6 km hiking trail to King Charles

III to commemorate his coronation in 2023. If that were not enough, there is

another trail dedicated by his mother the late Queen Elizabeth II in 2016. Who

knew?

Well we

shouldn’t be too surprised. Historically, the British like the Chouf. For most

of the 20th century the Ambassador kept a summer residence in Abey.

The British government decided to sell it in 2001 (reportedly to Walid

Jumblatt) but not before the body of Lady Hester

Stanhope was the famous 19th century British traveller, adventurer

and erstwhile spy, was exhumed from a corner of the garden. Her remains were

cremated and her ashes were scattered in the village of Joun, 10 km east of

Sidon, where she lived for three years before her death in 1839.

The Levant has always been a British espionage hub. T.E.

Lawrence, AKA Lawrence of Arabia, who learned Arabic in Beirut, famously

liaised with the Arab tribes against the Ottomans in World War I, while the

traveller, archaeologist and spy, Gertrude Bell, a modern day (and more

effective Hester Stanhope) helped create modern Iraq and the installation of

King Faisal.

But, possibly due to its sui generis character Lebanon,

and Beirut in particular, has always had a particularly strong lure for British

schemers and intelligence operatives be they the spies or the spied-on.

Three years after the death of Hester Stanhope, another

compatriot showed up in what is now Lebanon. The Englishman, Colonel Charles

Churchill, lived among the Druze and wrote Mount Lebanon: A Ten Years’

Residence from 1842 to 1852, a three volume work in which promised to

explain “the manners, customs, and religion of its inhabitants with a full and

correct account of the Druze religion”. It was from Lebanon that he plotted

with the British Jewish aristocrat, banker and philanthropist Sir Moses

Montefiore, to create a blueprint for a Jewish homeland in Ottoman territories.

A century after Charles Churchill left his mark in the Chouf,

another British army officer, General Sir Edward Spears, the minister to

Syria and Lebanon during World War II, was hopelessly bedazzled by the Lebanese

singer and wartime triple agent, Emira Amal Al Atrash, AKA Asmahan. His

infatuation became so obvious that he was nearly recalled back to Britain. In

his memoirs he wrote of the Druze princess, “she was and will always be to me

one of the most beautiful women I have ever seen. Her eyes were as green and

immense as the colour of the sea you cross on the way to paradise...Later, I

was to learn that she had a glorious voice…she bowled over British officers

with the speed and accuracy of a machine gun. Naturally enough she needed money

and spent it as a rain cloud scatters water.” When Asmahan died in a car crash

in Egypt in 1944, Spears is said to have laid a wreath at the crash site.

Three

years later in 1947, the Chouf village of Shemlan became the Middle East Centre

for Arab Studies, an Arabic language school run by the British until it was

closed in 1978 due to the civil war. Given the Lebanese predisposition to

paranoia and suspicion of the foreigner, it became known as the ‘spy school’, a

nickname given extra credence by the fact that in the early 60s George Blake,

the British double agent, studied Arabic there just before he was unmasked.

But

Blake is not as famous as Kim Philby, Britain’s most notorious traitor who

defected to the Soviet Union in January 1963 from Beirut, where Philby, then

working for both MI6 and as a correspondent for The Observer and The

Economist. Confronted by his old friend and fellow MI6 agent, Nicholas

Elliot, he knew it was time to disappear, or do a ‘fade’ as spies call it. He

sailed into exile aboard a Russian cargo ship docked in the Lebanese capital.

He died in Moscow in 1987.

Philby’s

name is forever associated with the glamour of post-independence Beirut,

spending his time gathering and dispensing intelligence in the bar (he was by

most accounts a heroic drinker) at the St Georges Hotel. It was a meeting point

for bankers, journalists, diplomats, oil men and spies and no doubt inspired a

trio of 60s spy movies. In “Where the Spies are”, the quintessentially English

David Niven played ‘our man in Beirut’, staying at the Alcazar Hotel (which

became a branch of HSBC opposite the ST Georges). In “Twenty Four Hours to

Kill”, released in the same year, Mickey Rooney met a sticky end amid the ruins

of Baalbek, and in 1972 Richard Roundtree and Chuck Connors chased the KGB

around Parliament Square in “Embassy”. Fabulous stuff!