It is September and we have survived the usual August chaos as well as the unusually hot temperatures, all exacerbated by a creaking infrastructure unable to sustain a local population, which has nearly doubled in the past 15 years, and the influx of nearly every Lebanese expat from Sao Paulo to Sydney and all stops in between.

They made the pilgrimage to the home country for a host of reasons, but normally it is to introduce their new families to their extended family and, in doing so, show the extended family how well they've done in whichever expatriate bolthole they’ve decided to put down roots.

They go to Baalbek and Byblos; Jeita and Batroun and there are nostalgic, arak-fuelled lunches ending with comedic, half-remembered attempts at a dabke. It’s all very jolly.

I see this a lot in my own village of Zabbougha in the North Metn, where Karams have lived for several centuries and where I was fortunate enough to inherit a house. With its one shop and three churches, the year-round population is a mere 300, a number that swells to almost double in the summer when the softer townies like myself move back.

Zabougha is not as affluent as the more manicured nearby villages of Kfaraqab and Ain el Qabou. Indeed, as late as the early 70s, my father’s house was one of a handful that had a toilet. Summers were spent throwing stones at goats, playing cards and swinging on old tires roped to branches. The men still wore the black baggy trousers or sherwel, women sat around and baked, and most homes had a donkey. You get the picture.

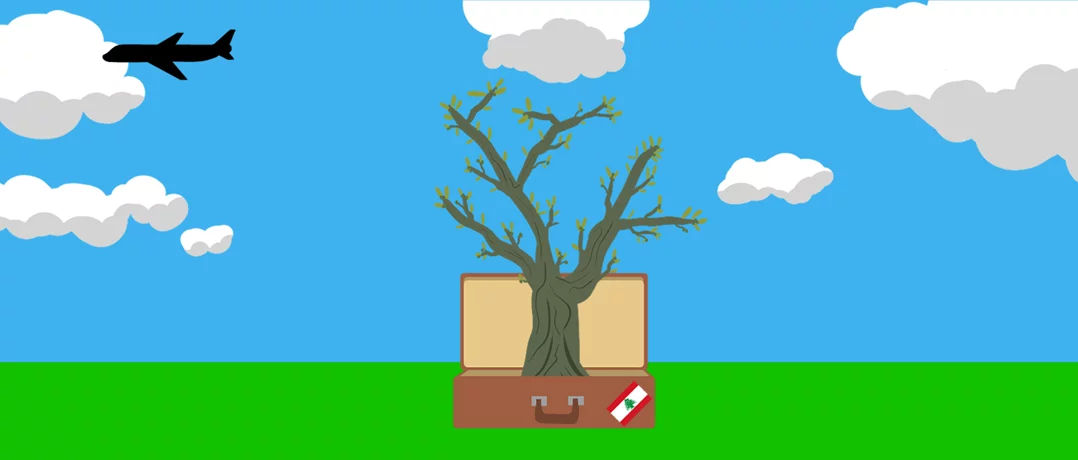

But I digress. The Lebanese have had to seek opportunities beyond their shores ever since the first Phoenician boat left the Levantine littoral to explore the then-known world. Laden with glass, wine, olive oil and the coveted purple murex dye, they established trading posts across the Mediterranean and created a trend that has endured ever since.

They were forced to travel because of political instability at home brought about by whichever tribe, race, or nation happened to be putting the squeeze on the region. So it was ever thus.

My grandfather, Esper Karam and his brother Selim, left Lebanon at the end of the 19th century. Like many thousands, they boarded boats, often not knowing the final destination, for a stab at a better life. They ended up in Brazil and, by all accounts, prospered. Later, after my grandfather returned to Lebanon just before the 1915 famine, and deposited his Swedish wife in Zabbougha, he went off to Mali in a bid to make more money. Mali would be no picnic today; imagine working there in the 1920s!

The 1975-190 civil war created a new exodus, mainly to Australia and Canada, but also West and central Africa, where we have made a name for ourselves as mighty traders.

And today, since COVID and the October 2019 Thawra, the brain drain continues. In a way, we should be thankful, because while we don’t want our sons and daughters forced into exile, their remittances represent 20% of a GDP that has been whittled down to $30 billion in the last five years. The diaspora is propping up an economy that Lebanon's political and banking class brought to its knees.

But I worry about Lebanon. I always have. Since independence in 1943, it has never been any one constant entity. Less a country and more of the weathervane for the rhythms of the region, its religious makeup has been a curse and a blessing in equal measure.

The late summer of 2024 saw the mortal wounding of Hezbollah and the long-overdue election of a new President and appointment of a Prime Minister. The general and the judge, two technocrats. A dream team? Maybe. But I also remember the summer of 1982, when Israel, again Israel, bludgeoned the PLO, an organisation which, like Hezbollah, divided (and to a certain extent controlled) the country, into leaving, on boats to Tunisia and Greece. Then, like now, the country also dared to dream. That is, until Bashir Gemayel, a young president who had been able to unite the country like no other president has done since, was blown to bits, and we had to wait another eight years until the guns fell silent.

Now the Aoun/Salam honeymoon is over and the government, under pressure by Israel and the U.S., is talking about disarming Hezbollah, and while we dare to hope, we quietly wonder, and fear, if this will tip us over the edge again.

In the meantime, the cliches roll on. The Lebanese continue to be their charming selves, shot through with status anxiety and an uncanny gift of not letting genuine existential threats get in the way of doing business and or having a good time.

And while we fight for a chance of a foothold at survival, happiness, health, and prosperity, I wait for the slight, imperceptible breeze that comes at this time of year to signal that the summer fever has broken, and autumn is upon us, a time when the leaves rustle and those few grapes left on the vine, shrivel and sweeten with excess sugar to remind us that life can be sweet.