Cabinet’s report hinges between success and postponement

Cabinet’s report hinges between success and postponement

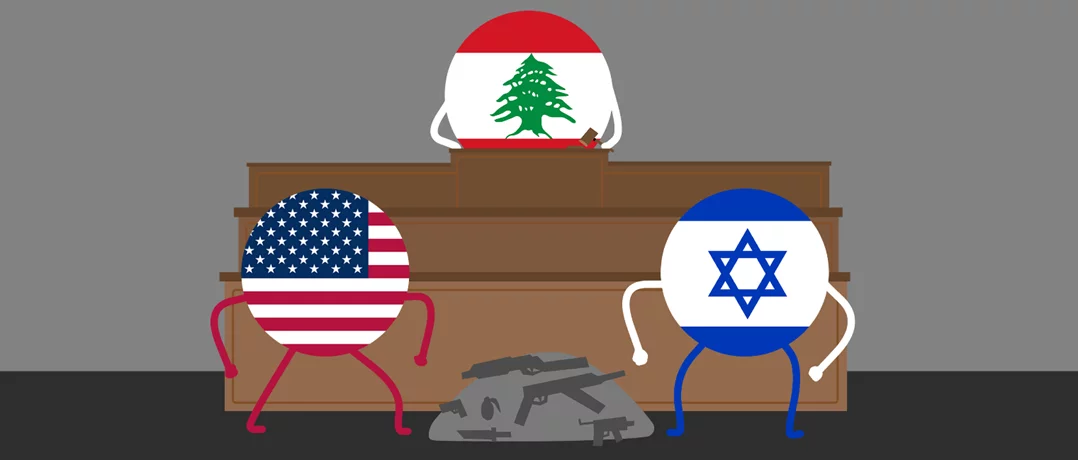

Lebanon has entered a sensitive new phase in its long-running struggle over state authority and armed non-state actors. On 8 January 2026, the Lebanese Council of Ministers met at the Baabda Presidential Palace, where the first item on the agenda was a report prepared by the Lebanese Army Command on its plan to implement the decision to place all weapons exclusively in the hands of the Lebanese state. The plan, known as “National Shield,” is based on a Cabinet decision taken on 5 August 2025.

In this context, the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) has announced that it has effectively taken control of security in the country’s south, a region that for decades has been under the dominant influence of Hezbollah. The announcement comes amid growing international pressure, continued Israeli military actions, and intense domestic debate over the future of Hezbollah’s weapons. While officials have described the move as a significant step toward restoring state sovereignty, its durability remains uncertain in a volatile regional and domestic environment.

A milestone in the South

According to the Lebanese Army, the first phase of a government-backed plan to restrict weapons to state institutions has been completed south of the Litani River, roughly 30 kilometers from the Israeli border. Military officials say operational control has been extended across most of the area, with the exception of positions still occupied by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). The army reported dismantling infrastructure, clearing tunnels and removing weapons belonging to armed groups (including Hezbollah and Palestinian militias), while continuing efforts to deal with unexploded ordnance left from years of conflict.

Crucially, the army’s deployment took place without notable clashes with Hezbollah. The group has claimed it complied with the November 2024 ceasefire that ended a devastating year-long war with Israel (which erupted on 8 October 2023, following the 7 October “Al-Aqsa Flood” perpetrated by Hamas against Tel Aviv) and withdrew its fighters from the area, although various local and international sources beg to differ. For the Lebanese state, however, this absence of confrontation has allowed the army to project authority in a region historically beyond its full control.

Israeli pressure and skepticism

The LAF’s announcement was quickly met with cautious reactions abroad.

Israel described the steps as “encouraging” but insufficient, accusing Hezbollah of attempting to rebuild its military capabilities with Iranian support. Israeli officials have repeatedly argued that the ceasefire requires the full disarmament of Hezbollah, a point Lebanon disputes, noting that the agreement is ambiguous beyond the Litani River.

Despite the ceasefire, Israel has continued near-daily strikes on targets it says are linked to Hezbollah and maintains control of at least 5 strategic positions in southern Lebanon. Meanwhile, Lebanese authorities argue that these actions violate the truce and undermine the army’s ability to consolidate control.

The next phase and its challenges

Attention is now turning to what comes next. Lebanese officials say the second phase of the plan will focus on the area between the Litani and the Awali rivers. Nevertheless, no timeline has been announced, reflecting both political sensitivity and practical constraints. The Lebanese army, already stretched thin, has repeatedly warned of limited funding and equipment, even as international donors condition reconstruction aid on progress toward disarming non-state groups.

The challenges become more complex north of the Litani. Hezbollah has made clear it will not discuss disarmament in other regions while Israeli forces remain on Lebanese soil and attacks continue. The group retains a strong presence in Beirut’s southern suburbs and the eastern Bekaa Valley, areas where any attempt at forced disarmament could risk internal conflict.

Political divisions at home

Lebanese President Joseph Aoun has firmly rejected the use of force against Hezbollah, warning that such a move could inflame sectarian tensions and destabilize the country. Hezbollah is not only an armed movement but also a political party represented in parliament and government, as well as a social actor providing services to large segments of Lebanon’s Shia community. Its supporters view its weapons as a deterrent against Israel, while opponents argue that the aftermath of the recent war proved its inefficiency and presents a rare opportunity to restore a state monopoly on arms.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister (PM) Nawaf Salam and other senior officials have endorsed the army’s gradual approach, emphasizing dialogue and institutional strengthening over confrontation. Yet critics, notably the Lebanese Forces (LF) party and its ministers who suggested 31 March 2026 as the deadline to achieve exclusivity of arms, contend that the absence of clear deadlines risks turning the disarmament plan into an open-ended process vulnerable to regional shifts and domestic paralysis.

In conclusion, the Lebanese army’s declaration of control in the south marks a notable, if incomplete, assertion of state authority in a region long shaped by conflict and parallel power structures. It reflects a cautious attempt to balance international demands, domestic realities and the ever-present risk of renewed war with Israel. Whether this effort evolves into a broader restoration of sovereignty or stalls amid political hesitation and regional tensions will depend on factors well beyond the battlefield.