A fragile diplomatic opening raises hopes for peace with Syria and Lebanon, but mistrust and outside influence cloud its prospects.

Can talks with Syria and Lebanon turn Israel’s battlefield gains into lasting peace?

Can talks with Syria and Lebanon turn Israel’s battlefield gains into lasting peace?

A sudden flurry of diplomacy has opened this week, what Israeli officials are calling a “window of opportunity” to convert battlefield gains into political arrangements along Israel’s northern frontiers. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu spoke of “progress” in talks with Syria, U.S. mediators confirmed that a limited “de-escalation” pact is nearly ready, and Damascus’ al-Sharaa said the outlines of an accord are taking shape. At the same time, Lebanon’s president Joseph Aoun stressed that peace must be built on justice, calling for a full Israeli withdrawal from Lebanese territory.

Lebanon’s Unresolved Dilemma

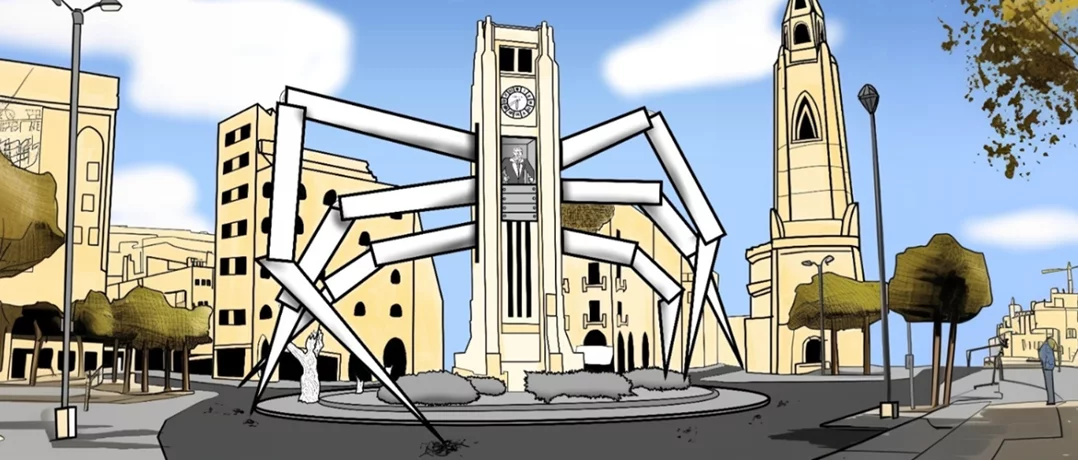

“The struggle over Lebanon’s identity, whether it will become a land of life and opportunity, a bridge connecting its people to the region and the wider world or descend into a battlefield that spreads conflict to its neighbors, remains fierce,” President Joseph Aoun said.

We have chosen the path of life and coexistence, and we will steadfastly pursue it

He stressed that protecting Lebanon is not just a national duty but a global responsibility, warning that if the country, where Christians and Muslims live together as distinct yet equal communities, were to collapse, the world would lose a unique model of coexistence.

Even as Syria and Israel edge toward a potential security agreement, Lebanon remains a critical variable. Hezbollah has long insisted it will not disarm while Israel occupies Lebanese territory or carries out strikes inside the country.

“We demand an immediate halt to Israeli attacks, the withdrawal of Israeli forces from Lebanese territory and the release of Lebanese prisoners,” Aoun told delegates at the 80th UN General Assembly in New York. He added that Lebanon “remains committed to being a platform and model for peace and coexistence, but it cannot do so under constant aggression.”

Political activist Makram Rabah told The Beiruter that

Lebanon is ill-prepared for serious negotiations. The problem is that the Lebanese from their end do not have a plan together. If you ask the Lebanese government what their strategy is and what is their file on peace, they have none. They don’t even have one on war. Peace is a homework that the Lebanese government, particularly the president, needs to prepare before going into any type of negotiations or even an extended ceasefire

Israel Pushes Leverage

Netanyahu, speaking to a cabinet session earlier this week, sought to frame recent military pressure as a potential opening for diplomacy. “Our victories in Lebanon against Hezbollah have opened a window to a possibility that wasn't even imagined before our recent operations and actions, and that is the possibility of peace with our northern neighbors. We are holding talks with the Syrians, there is some progress, but it's still a distant vision,” he said, signaling cautious optimism while stressing that a full agreement remains far off.

Those interests include retaining control over sensitive high ground near the Golan and ensuring that Iranian-backed militias cannot entrench themselves along Israel’s border.

Syria Signals Readiness

Damascus, meanwhile, is balancing relief from Israeli strikes with the risk of appearing to cede sovereignty. Syrian president Ahmed al-Sharaa told reporters: “Syria is ready to turn the page on cycles of retaliation if Israel respects our territory and our people. We are close to a framework that can bring calm, provided it is balanced and verifiable.”

But doubts remain. Rabah argued that despite Sharaa’s willingness, trust is scarce:

There’s a number of challenges to signing peace between Syria and Israel. The new Syrian regime wants to give compromises, yet at the same time it is not easy for a country that has fought Israel for so long to simply agree to peace. Given the fact that Ahmad Sharaa has a jihadi background, it makes it impossible for anyone to trust him, particularly the Israelis. At the end of the day, he may be willing to give a lot of concessions, but given what’s happening in Gaza and the Iranians’ unwillingness to give up Syria, there will be a lot of problems

Strategic Architecture and Risks

Diplomats familiar with the talks sketch out a predictable architecture: phased withdrawals tied to verifiable Syrian commitments, joint monitoring via UN or U.S. channels, and incident-forensics teams to prevent escalations spiraling out of control. But two questions loom: who will enforce violations, and what happens if non-state actors, from Hezbollah to Iranian units, ignore the deal?

Rabah suggested that a Syrian-Israeli agreement could indirectly influence Lebanon: “If the Syrians actually sign peace, this would encourage peace with Lebanon, of course, because we grew up under the saying that Lebanon will be the last country to sign peace, and indeed it is the case. Any talks about peace can play a positive role, but at this moment, I don’t think it’s even on the table.”

Sharaa himself acknowledged the challenge:

No agreement will survive if outside actors seek to sabotage it. The responsibility lies with all of us to restrain those who profit from war

Domestic Constraints

Each capital faces its own political trap. Netanyahu must show Israelis that concessions won’t compromise national security. Sharaa, leading a fragile Syrian transition, risks being portrayed as surrendering to Israel. And Aoun, who positions Lebanon as a victim of aggression, cannot be seen as giving away prisoners or territory without reciprocal guarantees.

Rabah noted that Lebanese-Syrian coordination could at least stabilize the frontier: “Coordination between Lebanon and Syria is very important to establish a kind of stability and normalize relations with the new regime. I don’t think that such relations can have direct repercussions on the talks about peace, because simply the Lebanese and the Syrians will not have a joint agenda to engage in peace with Israel. But having a kind of stable border between Lebanon and Syria, particularly also talking in normalization and figuring out the Shaba’a Farms controversy, is enough to help push peace in the right direction.”

For these reasons, diplomats predict that what emerges in the coming weeks is more likely to be a pragmatic ceasefire-plus arrangement than a sweeping peace treaty. “We are not talking about Camp David here,” the U.S. envoy said. We are talking about stabilising a front and saving lives

Historical Context

Israel’s relations with Lebanon and Syria have long been defined by conflict and mistrust. Lebanon and Israel fought multiple wars, including the 1982 invasion and repeated clashes with Hezbollah, while Israel and Syria have contested the Golan Heights since 1967. Earlier peace initiatives, including the 1990s Madrid talks and the 1994 Israel-Jordan treaty, largely bypassed direct Israeli-Lebanese or Israeli-Syrian negotiations, leaving borders and security unresolved.

Lebanon’s peace history has been fraught. President-elect Bachir Gemayel in 1982 resisted a treaty without Arab consensus. His successor, Amine Gemayel, signed the U.S.-brokered May 17 Agreement in 1983, only for it to be annulled a year later under Syrian pressure. Post-civil war, the 1989 Taif Accord and Lebanon’s role in the 1991 Madrid Conference reinforced a cautious stance. The Israeli withdrawal in 2000 and the 2006 war with Hezbollah underscored armed deterrence over diplomacy. In recent years, President Michel Aoun briefly floated peace talks in 2020, opposed by Hezbollah, while the 2022 U.S.-mediated maritime border agreement marked a rare direct negotiation. Today, de-escalation and technical agreements reflect the delicate balance of history, strategy, and opportunity.

The next stage will determine whether Israel, Syria, and Lebanon can turn cautious dialogue into a durable peace. Beneath the cautious optimism, however, a pressing question remains: how much of Israel’s “window of opportunity” is driven by its own strategy, and how much is guided from Washington, shaping the timing, terms, and stakes? In a region where history has repeatedly betrayed hope, the real challenge will be whether this fragile opening can endure not only the battlefield but also the invisible lines of influence stretching far beyond the Levant.