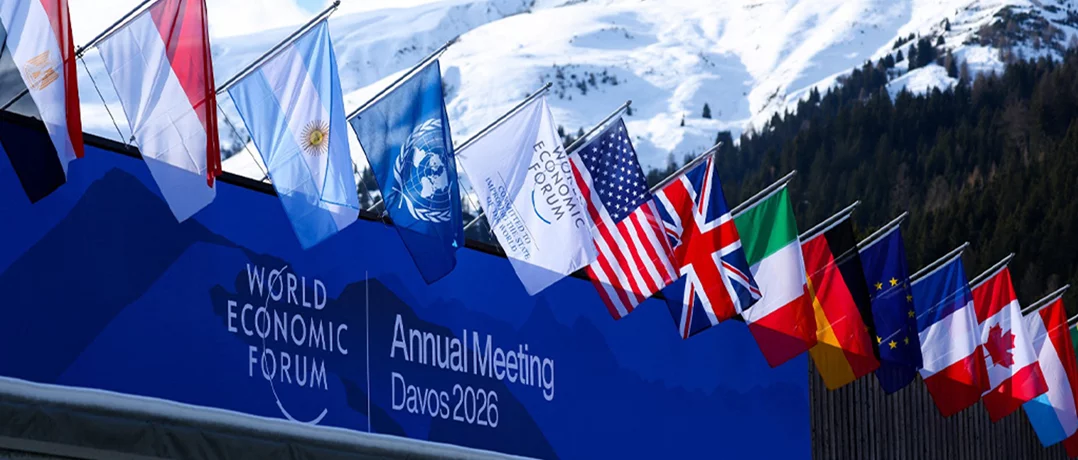

Davos 2026 convenes global leaders at a moment of deep geopolitical flux, testing whether dialogue can still shape outcomes in a fractured, high-stakes world.

Davos 2026: Can a “Spirit of Dialogue” still shape a fractured world?

Davos 2026: Can a “Spirit of Dialogue” still shape a fractured world?

When global leaders descend on the Swiss Alps this January, they will arrive in a world more fractured, volatile, and technologically disrupted than at any point in recent decades. From January 19 to 23, 2026, the World Economic Forum (WEF) will convene its 56th Annual Meeting in Davos, bringing together nearly 3,000 political, business, and civil society leaders under a deceptively simple theme: “A Spirit of Dialogue.”

The choice of words is revealing. Davos 2026 comes at a moment when dialogue itself appears increasingly fragile, strained by geopolitical rivalry, economic fragmentation, accelerating technological change, and declining trust in institutions. Organizers describe the meeting as an impartial platform for cooperation and long-term problem-solving. Critics counter that Davos has perfected the language of consensus without consistently delivering concrete outcomes.

Still, the stakes this year are unmistakably high.

Why Davos feels different in 2026

Davos 2026 is unfolding amid rare geopolitical flux and institutional transition, positioning it as a forum of multiple firsts. Central to this shift is the return of U.S. President Donald Trump to the global stage. This marks his first in-person appearance at Davos during a second term, and the scale of the U.S. delegation is widely interpreted as a deliberate statement of intent.

The geopolitical environment has grown markedly more complex. Trump’s policies, ranging from aggressive tariff strategies to blunt positions on Iran, Greenland, and the broader Western Hemisphere, have unsettled long-standing assumptions about U.S. leadership and multilateral cooperation. How these ambitions are debated, defended, or challenged in Davos corridors will be closely watched, particularly as Washington has stepped back from major frameworks such as the World Health Organization and key climate agreements.

This will also be the first Davos since Venezuela’s dramatic political rupture on January 3, when Nicolás Maduro was removed from power. Opposition figures have long used Davos as a lobbying platform, but this year attention has intensified around what a potential reopening of Venezuela could mean for energy markets, sanctions, and regional stability. The moment recalls earlier Davos debates dominated by Russia’s war in Ukraine, while raising fresh questions about how U.S. ambitions in the Western Hemisphere will now be framed.

The Forum will, for the first time, host a new generation of United Nations leadership, including the heads of the UN Development Program and the UN Refugee Agency. They arrive amid severe funding crises following cuts by major donors such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany. Although Washington later announced a $2 billion aid package, humanitarian funding gaps remain acute. For many UN leaders, Davos offers rare proximity to private-sector power brokers, echoing moments such as Bill Gates’ $750 million pledge to launch Gavi at Davos in 2000.

Regionally, Davos 2026 marks a historic turning point for Syria. For decades, Damascus viewed the Forum through the former regime’s “anti-imperialist” lens and remained openly hostile to it. While Syrian officials occasionally attended in the past, presidents never did. That changed following the fall of the Assad regime in December 2024. Syria’s foreign minister, Asaad Al-Shibani, appeared in Davos weeks later, interviewed on stage by former UK prime minister Tony Blair. Since then, Syria has taken decisive steps away from the Iranian axis, placing Damascus firmly on Davos’ geopolitical radar.

Additional firsts are expected. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi will attend Davos for the first time, while the Gaza Peace Board is scheduled to convene during the meeting. Historically, Davos has served as one of the few neutral venues where Palestinians and Israelis could meet quietly and off the record, an informal role that may again prove critical amid fragile ceasefire efforts.

Hovering over the entire gathering is a symbolic absence: this will be the first Davos without its founder, Klaus Schwab. This decision follows allegations of financial and ethical misconduct against Schwab and his wife, which led to his retirement as chairman with immediate effect. The WEF board has supported an independent investigation into these allegations, which surfaced shortly after the announcement of Schwab's retirement. Opinions about Schwab remain deeply divided, yet few dispute that he built an institution whose convening power and relevance have endured for more than half a century.

A forum born in the Alps and built for power

Founded in 1971 by economist Klaus Schwab, the World Economic Forum began as a modest gathering of European business leaders. Over five decades, it has evolved into the world’s most visible, and most contested, convening of global power.

What started in a ski resort of roughly 10,000 residents has become an invitation-only summit addressing issues ranging from economic inequality and climate change to war, trade, and artificial intelligence. Davos 2026 will feature more than 200 sessions spanning geopolitics, finance, technology, climate resilience, and social cohesion.

Organizers say this year’s meeting will host a record number of political leaders, nearly 400 senior officials, including more than 60 heads of state and government. Headlining the event is U.S. President Donald Trump, who will deliver a keynote address and arrive with the largest U.S. delegation ever to attend the Forum. He will be joined by senior members of his administration, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent.

European leadership will be strongly represented, with French President Emmanuel Macron and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen expected to attend. Beyond the transatlantic axis, leaders such as Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Canada’s Mark Carney, China’s Vice Premier He Lifeng, and Congo’s President Félix Tshisekedi underscore Davos’ global reach.

The corporate presence is equally formidable. Nearly 850 chief executives and chairpersons will attend, including technology leaders such as Nvidia’s Jensen Huang, Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis, and Mistral AI’s Arthur Mensch. International institutions will also feature prominently, with figures such as NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte and WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala shaping discussions on security and global trade.

From buzzwords to pressure points

This year’s “Spirit of Dialogue” is structured around five pillars: cooperation, growth, investment in people, innovation, and prosperity. Sessions will explore how to restore cooperation in a world of fractured alliances, manage geopolitical risk, and pursue growth within planetary boundaries. Climate resilience, energy security, water systems, and nature protection are expected to feature prominently.

Yet skepticism remains a persistent undercurrent. Critics argue that Davos risks becoming an echo chamber of elite concern, rich in dialogue but poor in enforcement. The Forum counters that its role is not to govern, but to convene, creating space where deals, coalitions, and ideas can emerge beyond the constraints of formal diplomacy.

As Davos 2026 opens, the central question is no longer whether the world needs dialogue, but whether dialogue alone is sufficient. With wars unresolved, inequality widening, and technology advancing faster than regulation, the Alpine gathering faces a renewed test of relevance: what, if anything, changes once the leaders leave?