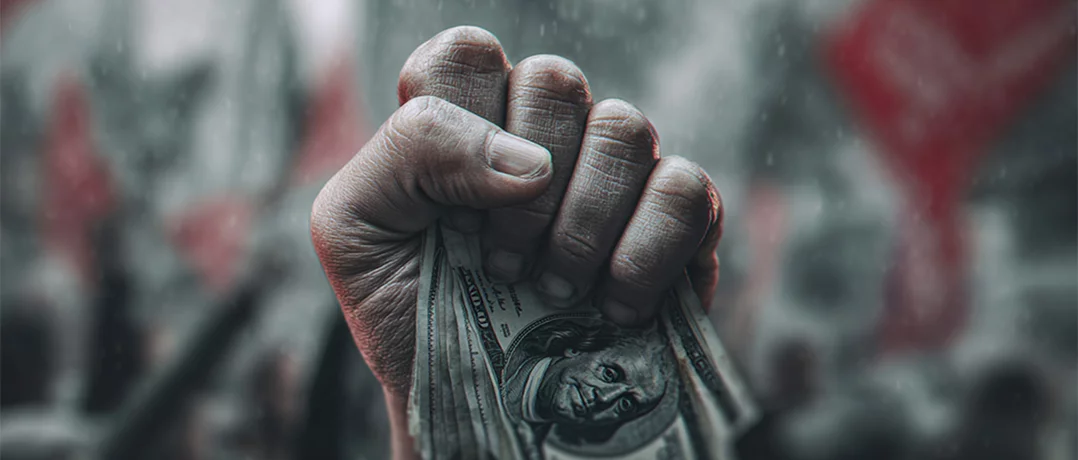

Public anger flared across Lebanon after the Cabinet approved new VAT and fuel taxes, with protesters warning the hikes shift the cost of reform onto citizens already strained by inflation and the financial collapse.

Fuel and VAT hikes in Lebanon spark protests across the country

Fuel and VAT hikes in Lebanon spark protests across the country

Anger spilled onto the streets a day after Lebanon’s Cabinet approved a series of tax increases.

At fuel stations across the country, 95-octane gasoline was selling for 1,785,000 Lebanese pounds (approximately $20), while 98-octane reached 1,828,000 Lebanese pounds (approximately $20.50). The increase came less than 24 hours after the Cabinet approved a one percentage-point rise in value-added tax (VAT) and imposed an additional 300,000 Lebanese pounds (about $3.30) on gasoline.

The government says the new taxes are needed to finance grants for public sector employees whose wages and pensions were eroded by the financial collapse that began in 2019.

Prime Minister Nawaf Salam said the Cabinet had little choice but to raise gasoline prices but decided against increasing diesel costs to avoid further burdening lower-income groups. “We want public servants to receive their rights,” he said.

On the streets, however, the backlash was immediate.

Several roads were blocked by protesters who say the decision once again shifts the cost of reform onto ordinary people. For some demonstrators, the scenes evoked memories of the 2019 uprising, when hundreds of thousands took to the streets against the ruling political class.

For Vivian Abdelkhalek, the issue is not whether public servants deserve support. Her husband is a retired soldier.

“I came to oppose this decision because it’s extremely unfair,” she said, standing among a group of demonstrators. Although her family will technically benefit from the raise, she said the increase about $80 is meaningless compared with the cost of living.

Her husband’s pension is $280 a month. The family of six has two children in university, one in high school and one in elementary school. Their rent alone is $400.

“When fuel goes up, everything goes up,” she said. “Even bread becomes more expensive. Even water!”

Healthcare, she added, is theoretically covered for military families. In practice, however, many medicines are unavailable, forcing them to pay out of pocket and wait for reimbursement. Compensation her husband received before 2019 was wiped out during the banking crisis. Payments issued afterward, she said, “couldn’t even buy a bicycle.”

They’re giving us $100 with one hand and taking $200 with the other.

At the same protest, 22-year-old university student Ahmad Daher expressed frustration over what he described as the unfair distribution of the economic burden.

“I’m forced to work to continue my studies,” he said. “I already spend half my salary on transportation. If fuel becomes more expensive, transportation will increase, and so will other living expenses. Everything will go up, and it will all be paid by us.”

He argued that reforms should focus on progressive income taxes, customs duties and maritime properties not consumption taxes that affect everyone equally, regardless of income.

Because Lebanon depends heavily on imports and private transportation, hikes in gasoline prices quickly ripple through the economy, driving up the cost of food, services and everyday goods. With most families already struggling and social support limited, even minor tax increases can place significant strain on households living paycheck to paycheck.

According to the Gherbal Initiative, a nonprofit civil society organization that aims to make data visually accessible to the public, imposing a 300,000 Lebanese pound (about $3.30) tax per can of gasoline could generate about $486 million annually, while a one percentage-point increase in VAT would bring in roughly $188 million more from consumers. Combined, the two measures would collect approximately $674 million, or around 2% of Lebanon’s projected annual income.

Despite the anger, turnout was limited far smaller than the crowds that filled Lebanon’s streets in 2019. Daher said he had expected more people to show up.

“I’m very disappointed,” he admitted. “But I will continue.”

For many Lebanese, the frustration is less about one percentage point of VAT or a single fuel hike and more about what they see as a recurring pattern. Since the financial collapse, purchasing power has evaporated, savings have been trapped in banks and public services have deteriorated.

Each new increase, they say, does not solve the system’s problems. It simply makes daily survival harder, one step at a time.