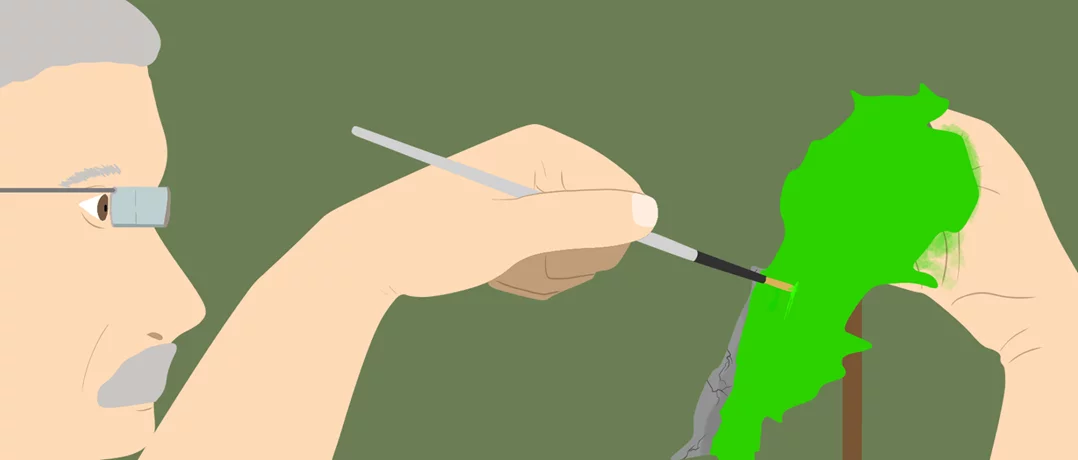

Lebanon’s 1943 independence arose from unified resolve and global pressure, unlike today’s fragmented politics and weakened sovereignty

Independence revisited: How Lebanon’s past rhymes with its present

Independence revisited: How Lebanon’s past rhymes with its present

Lebanon’s 1943 independence did not emerge in a vacuum. It was the outcome of a deliberate convergence between an internal resolve for self-determination and an external environment increasingly receptive to the country’s aspirations.

As Lebanon marks another Independence Day, the moment offers an opportunity to revisit the intricate relationship between domestic cohesion and resolve as well as foreign influences that shaped the nation’s early path to sovereignty.

This article examines how President Bechara el-Khoury and Prime Minister Riad el-Solh forged an unusual moment of internal cohesion, and how their efforts overlapped with broader diplomatic shifts involving Britain, the United States, and regional actors. Independence, we argue, was not the triumph of national will alone, nor the mere result of shifting global interests; it was the product of both.

Yet the discussion does not remain confined to history. Drawing from this historical lens, we then turn to the present, where the fragmented political landscape, erosion of public trust, and evolving geopolitical dynamics challenge Lebanon’s ability to safeguard its own independence.

Through an in-depth and exclusive interview with the esteemed Lebanese constitutional scholar, Dr. Antoine Messarra, we confront a pressing and uncomfortable question: Is Lebanon truly independent today? By examining both past and present, we seek to understand what independence once required, and what its reclamation would demand in our time.

How internal and external factors converged during Lebanon’s 1943 self-determination

Before the infamous independence of November 22, 1943, a series of pivotal developments laid the groundwork for Lebanese self-determination.

Following the 1943 parliamentary elections, an “independent constitutional government” was formed on September 25, 1943, by Prime Minister Riad el-Solh, who was appointed by the newly elected President Bechara el-Khoury. Around this period, an unwritten agreement between Christians and Muslims was adopted. Known as the “1943 National Pact,” it articulated a formula for coexistence among the Lebanese within a free and independent Lebanon. The Pact drew from Khoury’s presidential address and Solh’s ministerial statement delivered before Parliament; with the latter serving as a “Declaration of Independence.”

Lebanon’s various political and sectarian components took a firm and decisive decision to form and join a sovereign Lebanese state hand in hand, which had already been established in 1920. Based on the Cabinet’s draft bill, Parliament convened on November 8, 1943, to amend the 1926 Constitution and remove all articles contradicting full independence; however without notifying the French. This move sparked severe backlash. France retaliated by issuing decisions No. 464 and 465, annulling the amendments, dissolving Parliament, suspending the Constitution, and forming an alternative government under Emile Edde. Military units were also dispatched to arrest the Lebanese president, prime minister, 3 ministers (Camille Chamoun, Adel Oussairan and Salim Takla) as well as the Member of Parliament Abdel Hamid Karame at dawn on November 11, 1943. The detainees were taken under heavy guard to an unknown location, later revealed to be the Citadel of Rashaya (known as the “Citadel of Independence” or the “Fort of November 22”).

Instead of surrendering or yielding, the Lebanese political leaders and wider public rallied around the country’s legitimate authorities and stood steadfast in support of their right to self-determination. General strikes, popular demonstrations, and even a clandestine newspaper titled “Question Mark” (?) emerged in defiance of the French; a second question mark (??) was later added as the French issued a similar newspaper carrying the exact same mark to convey their message and promote their propaganda against the national movement. Meanwhile, Ministers Habib Abi Chahla and Majid Arslan, alongside Parliament Speaker Sabri Hamadeh, announced the formation of a provisional government in the village of Bshamoun, issuing essential decrees and orders, which even the Board of Directors of the Bank of Syria and Lebanon (Banque de Syrie et du Liban) followed. Simultaneously, Parliament met (despite the French siege) and unanimously approved key decisions, most notably adopting a new Lebanese flag (hastily drawn on a sheet torn from a school notebook), distinct from the French tricolor, with the Cedar placed at its center.

Interestingly, French authorities attempted to divide the Lebanese leadership in hope of creating disunity, hence inducing the desired capitulation. General Georges Catroux met President Khoury in Beirut on November 18, 1943, presenting proposals that the latter categorically rejected. These included releasing the detainees and reinstating him as president while appointing a new government, or having Riad el-Solh issue an apology to the French authorities and withdraw the constitutional amendments (with the possibility of re-amending the Constitution later in agreement with France). After failing to weaken Khoury’s resolve (who had coordinated with Solh regarding their mutual positions), Catroux sought to conclude a treaty with the Bshamoun government as a quid pro quo for the release of the Rashaya detainees, but the provisional government refused, demanding their unconditional release and reinstatement before any negotiations.

Beyond national resolve and local efforts, Lebanese appeals to foreign powers, combined with the evolving international dynamics, also aided in achieving the 1943 independence. Both Parliament and the provisional government sent protest memoranda to select foreign and Arab states (including representatives of major powers) who in turn exerted mounting pressure on the French.

The British chargé d’affaires in the East, Richard Casey, arrived in Beirut on November 19, 1943, and immediately met Catroux, delivering a British ultimatum demanding the replacement of Jean Helleu (the Senior Delegate of Free France in Syria and Lebanon) and the release of all detainees. If these demands were not met by 10:00 a.m. of November 22, 1943, the British Resident Minister in the Middle East threatened to declare martial law in Lebanon. The latter would place the country under the authority of the Commander-in-Chief of British forces in the Near East or his representative, the commander of the Ninth Army, who would then proceed to liberate the detainees. Indeed, Britain began deploying military reinforcements from Egypt to declare martial law in Lebanon by November 21, 1943.

Syria’s Foreign Minister, Jamil Mardam Bey, confirmed that UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill sought American assistance to expel France from the East. Britain and the United States jointly pressured Free France into granting Lebanon independence, threatening otherwise to refuse recognition of the French National Committee for Liberation. This struck Free France at a sensitive point since Free France’s primary concern was freeing its country from Nazi Germany’s occupation. Without Anglo-American recognition, however, it would face tremendous difficulty in liberating its own territory. Simultaneously, Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said called for a joint Arab military intervention in support of the Lebanese.

As the British-imposed deadline approached, leaving Catroux only hours to take measures that would save France from humiliation, the latter telegraphed the French Committee in Algeria, expressing his conviction that France must avoid escalation and being drawn into dangerous ventures. On this basis, all detainees were released before noon on November 22, 1943, allowing the legitimate government to return to Beirut and resume its work. That day, the French flag was lowered and replaced with the Lebanese flag atop the Parliament and the Grand Serail buildings, inaugurating Lebanon’s National Independence Day.

From here, Lebanon’s path to independence in 1943 emerged from a convergence of internal resolve and shifting geopolitical conditions. France’s prolonged and increasingly restrictive mandate, culminating in the arrests and clashes of November 1943, intensified national resentment and strengthened a growing sense of Lebanese unity. The rise of a shared national consciousness, embodied in the 1943 National Pact and the constitutional amendments of that year, was reinforced by widespread public pressure, including communities that had previously viewed the mandate more favorably (notably the Maronite Christians). At the same time, France’s weakening position during World War II (1939-1945) reduced its ability to maintain control abroad, especially as it was exhausted financially, logistically, and militarily. Additionally, the reliance of de Gaulle’s Free France on foreign military backing to liberate Paris from Nazi Germany’s occupation (achieved in late August 1944, following the decisive Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944) left little room for maneuver, prompting French submission to US and British demands (who were themselves eager to expel Paris’ influence in the region). This internal momentum intersected with mounting international pressure from Britain, the United States and several Arab states, whose diplomatic efforts (and in London’s case, even the threat of military intervention) pushed decisively for an end to the French mandate in Lebanon.

Is Lebanon truly “independent” today?

In an exclusive interview with The Beiruter, Dr. Antoine Messarra, former member of the Lebanese Constitutional Council (2009-2019) and a prominent constitutional expert in Lebanon, believed that

Lebanon today does not celebrate an ‘Independence Day,’ but an ‘Independence Commemoration,’ because we live in a country that is not independent.

He claimed that “the Lebanese are being distracted with secondary matters, while the core issue is the following: Lebanon now exists as two states: an official but symbolic state, and a parallel state with its own army and diplomacy. Everything else is merely diversion from the essence.” Therefore, he argued that “to use the phrase ‘Independence Day’ is, in fact, an insult to us, since we are not independent; we are effectively in a state of proxy occupation. I do not wish to accuse anyone, but we are a member (indeed a founding member) of the Arab League, not of the Iranian axis. Hence, we only observe an ‘Independence Commemoration,’ with no official celebration whatsoever.”

Messarra recalled that in 2020, Le Monde described how Lebanon has become an ungovernable monster; in an article titled “Liban: l’Etat, monstre ingouvernable.” From there, he outlined the conditions for rational governance in Lebanon, which are as follows:

- First, a Maronite President who carries the constitutional charter (in the manner of the late President General Fouad Chehab).

- Second, governments that do not violate the principle of separation of powers.

- Third, a constitutional culture among the people.

Although the aforementioned culture “exists in our daily life,” he argued that Lebanon still “suffers from confusion and intellectual clutter in approaching the Lebanese Constitution in a realistic, practical, and normative manner.” Messarra stressed that “Lebanon’s constitutional heritage is largely ignored, even by specialists.” In a meeting that gathered leading experts in law and constitutional studies, they asked: “Why does the preamble of the Constitution not define what the National Pact or ‘coexistence’ mean?” Messarra objected at the time claiming that “neither I nor any of us nor even the President of the Republic can define their meaning; the latter are defined by the founding fathers of the Lebanese Constitution; Kazim el-Ṣolḥ, Riaḍ el-Solh, Bechara el-Khoury, Michel Chiha, and the Lebanese Forum (al-Nadwa al-Lubnaniyya).” For that reason, he argued that we should not be seeking to clarify these concepts, since they had already been clarified within Lebanon’s constitutional heritage, but rather to “enrich them through comparative academic research in today’s world” as well as to re-anchor public understanding in the works and vision of the founding fathers.

Regarding the independence of 1943, Messarra advised the Lebanese to read the works of Fares Yassine, Nawaf Salam and Ghassan Tueni, among others. He said that “they reveal Lebanon’s deep heritage in defending freedoms and independence, and show that the independence of 1943 was the fruit of a long, continuous Lebanese struggle.” Despite this fact, in a recent meeting with Prime Minister Nawaf Salam, Messarra admitted that “we were astonished by how absent Ghassan Tueni’s legacy has become in Lebanese public life. Therefore, we must strive to revive Lebanon’s deeply rooted heritage; found in libraries, though absent from people’s minds.”

Moreover, Messarra warned of a persistent “Sublime Porte complex,” a historical, psychological tendency to seek external patrons rather than strengthen national institutions. He urged a return to Lebanon’s constitutional roots, enriched through comparative research but grounded in its original vision.

The core challenge: joining the state

According to Dr. Messarra, “Lebanon today resembles 1920, when Greater Lebanon was proclaimed on September 1.” At that time, “all sects and regions joined the new state.” Today, however, although “we face a similar situation, with all Lebanese aligning with the state,” he believed that “one Lebanese faction, with its own army and diplomacy, prefers defeat against Israel rather than joining this state.” He argued that “reducing the problem to disarmament trivializes the issue, for the core challenge remains the faction’s refusal to join the state.”

Messarra asserted,

Joining the state is neither a defeat nor a victory!

Indeed, engaging with the Lebanese state should not be treated as a transactional process, measured by gains and losses. It is, rather, a genuine national duty that all Lebanese are called to uphold. The state, as distinct from the governing regime, exercises 4 core sovereign prerogatives, as outlined by Messarra:

- The monopoly of organized force.

- The monopoly of diplomatic relations.

- Tax collection.

- Management of public affairs.

From here, “only the state,” he emphasized, “can legitimately maintain an army and conduct diplomacy”; which is not the case nowadays.

Furthermore, Messarra noted that “the Lebanese lack a culture of statehood,” something he believed must be cultivated through education and civic practice. He also noted that “we need a culture of ‘prudence’ (phronesis, in Aristotle’s terms): the capacity to weigh political risks and avoid greater dangers.” In politics, he continued, “choices are often not made between what is good and what is bad, but between what is bad and what is worse.” It is precisely this deficiency, he argued, that led Lebanon to repeatedly fail to seize critical opportunities for stability and unity.

Leveraging international conditions: a window not to be missed

If the 1943 Independence proved anything, it is that national resolve and efforts alone are insufficient (despite their importance and necessity). Acknowledging and navigating through favorable international circumstances must also be leveraged, as it represents another key pillar not to be underestimated.

Today, Dr. Messarra believed that “we have a unique moment not seen in 50 years: a president who upholds the Constitution, a functioning government (not a mini-parliament in disguise) and a broad international consensus (Arab, American, European and global) on stabilizing Lebanon.” He claimed that “ironically, we used to speak of ‘Lebanon as the arena,’ and now we have become ‘Lebanon of many arenas,’ posing a danger to the world. But the Lebanese are unaware of this. Terrorism extends through parallel entities operating outside the state, financed and armed from abroad. Any armed, foreign-funded non-state actor, with its own army and diplomacy, becomes a terrorist organization.” Thus, he added that today “there seems to be a strong global push to strengthen the central state, which curbs manifestations of terrorism worldwide.”

Furthermore, although we have exceptionally favorable international conditions, Messarra warned against relying on Israel to resolve Lebanon’s internal crisis. He claimed that it “is extremely dangerous,” given that “Israel thrives on exacerbating problems.” He added that Tel Aviv’s historic “project in Lebanon is partition and the destruction of the country’s structure and formula, not merely occupying land. This was one of the reasons behind Lebanon’s wars. Many authors have not read the correspondence between Moshe Sharett and David Ben-Gurion on how to partition Lebanon; the wars in the country were part of implementing this vision.” Messarra compared the moment to October 13, 1990, cautioning that seeking external forces to resolve internal divides leads to long-term dependency and deeper fragmentation. He claimed that, back then, “President Elias el-Hrawi kept negotiating with General Michel Aoun (then head of a transitional military government) in an effort to avoid calling on the Syrian army to end the rebellion. Ultimately, however, Hrawi was compelled to resort to Syrian intervention, which in turn further entrenched both his own dependence, and that of Lebanon, on Damascus.” Messarra ended by saying, “Today we face the same predicament: should we wait for the Israeli army to resolve Lebanon’s dual-state problem?”

When history rhymes

Mark Twain once observed,

History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

Lebanon’s 1943 independence was neither accidental nor exclusively homegrown. It emerged from a rare synchronization of internal unity, sincere determination, and a favorable international environment to achieve the required change. National leaders resisted pressure, citizens mobilized in unprecedented solidarity, and global powers (driven by wartime and strategic considerations) exerted the decisive leverage needed to break the French Mandate’s grip. Most importantly, there was a broad Lebanese consensus regarding joining an independent and sovereign Lebanese state, living side by side in respect and equality. Independence, in other words, was achieved when internal coherence met the right international moment.

Today, Lebanon confronts a set of challenges and opportunities that, while different in form, echo those critical moments in its earlier history. Indeed, as Dr. Messarra observed, Lebanon has yet to achieve true sovereignty: parts of its territory remain under Israeli occupation, Hezbollah and certain Palestinian factions continue to maintain armed structures that operate alongside (and at times outside) the authority of the state, the country’s economic, financial and political foundations have been severely eroded, while external actors continue to exert significant influence and intervene (whether through diplomatic pressure, economic leverage, or direct military involvement) in Lebanon’s internal affairs. Yet alongside these pressures lie conditions that could prove constructive. The international environment is, in some respects, more attentive to Lebanon’s stability and reform needs, and domestically, there are potential openings, if strengthened and properly developed, that could support a more secure and sovereign future. Should the country’s leaders and citizens carefully understand these dynamics, harness internal unity, and engage wisely with the international community, there exists a real possibility to achieve renewed and lasting independence; one shaped by lessons from history and adapted to the realities of our time.

In short, history does not repeat itself, but its lessons endure. Recognizing how these internal and external forces interacted in the past can help us avoid familiar pitfalls and seize the openings available today, possibly writing a better verse for the future. Only then can Lebanon move from commemorating independence to genuinely reclaiming and celebrating it.