In Lebanon, January 6 remains a living celebration of Christmas and Epiphany, shaped by faith, memory, and shared tradition.

Jan 6: When Lebanon’s Christmas tells a different story

Jan 6: When Lebanon’s Christmas tells a different story

While much of the world has already packed away its Christmas trees, for many in Lebanon, the season is not over. On January 6, churches are still full, bells still ring, and families are still gathering, not out of delay, but tradition. In Lebanon, Christmas does not end on December 25. For Armenians and for many Christian communities observing Epiphany, January 6 remains one of the most meaningful dates of the Christian calendar.

This coexistence of dates is not confusion. It is history.

Why Armenians celebrate Christmas on January 6

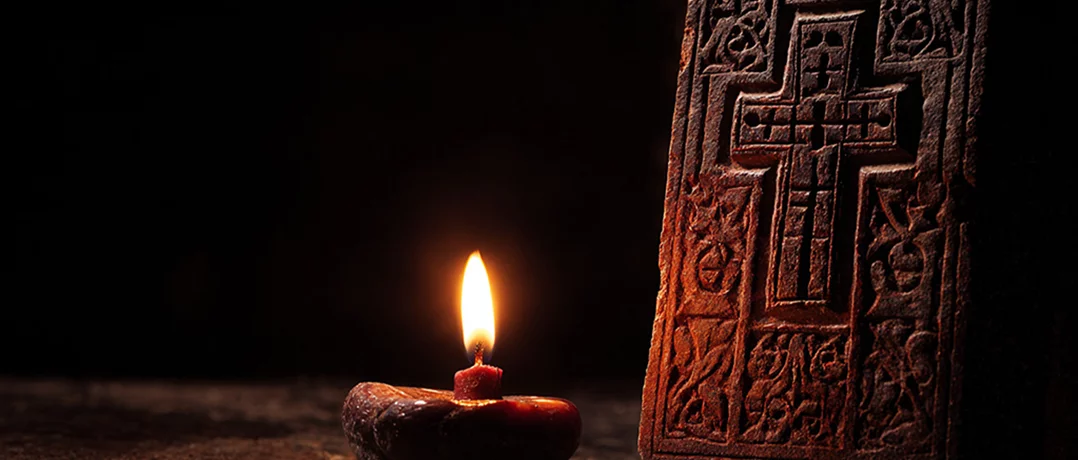

In the earliest centuries of Christianity, the birth and baptism of Jesus Christ were celebrated together on January 6, a feast known as Epiphany. It marked Christ’s manifestation to the world, his Nativity and his baptism in the Jordan River.

This unity changed in the 6th century, when Roman Emperor Justinian I officially separated the feasts. Christmas was set on December 25, while Epiphany remained on January 6. Most Christian churches adopted this division.

The Armenian Apostolic Church did not.

Armenians preserved the original tradition, continuing to celebrate Christmas and Epiphany as one feast on January 6. For Armenian communities in Lebanon, this date is not an alternative Christmas, it is the original one. Church liturgies, candlelight services, and family gatherings emphasize the spiritual meaning of the birth of Christ rather than the festive spectacle that later came to dominate December 25 celebrations.

In Lebanon, where the Armenian presence is deeply rooted, January 6 stands as a living reminder of Christianity’s earliest rhythms and of the country’s layered religious history.

Epiphany in Lebanon

In Lebanon, Epiphany has always been lived inside the home as much as inside the church. Beyond its religious meaning, it carried a calendar of gestures meant to protect the household through the heart of winter and bless the year ahead.

Kitchens filled with the smell of sweets prepared especially for the night: awamat, zalabiyeh, maakaroun, galette des rois and simple homemade pastries shared with family and neighbors. Many Lebanese families believe that Christ passes through homes at midnight to bless them. Doors were left open, lamps kept lit, and everyone tried to stay awake. Falling asleep means missing the moment of blessing.

One of the most familiar Epiphany rituals was repeating “Dayem, dayem”, may it last. Women would stir the winter provisions kept at home: flour, lentils, bulgur, dried fruits, asking that they be blessed and sustain the family until the end of the season.

Other traditions followed. Families prepare new yeast starter for the year, often shaped by the youngest child in the house, marked with the sign of the cross, and sometimes filled with a coin as a sign of abundance. It is hung overnight on a nearby tree to become the family’s blessed leaven for the year ahead.

After Epiphany Mass, families carry home blessed water. It is drunk by the sick, sprinkled in rooms, wells, and animal shelters, and carefully kept for moments of illness or fear. Many families also choose this day to baptize their children, reinforcing Epiphany as a feast of renewal, protection, and new beginnings.

In a country shaped by multiple calendars, confessions, and histories, January 6 reflects something uniquely Lebanese: the ability for different traditions to coexist, overlap, and endure.