Why Christmas crèches remain public in Lebanon while fading from Western public spaces.

Lebanon’s enduring crèche

Across much of the Western world, the Christmas crèche has gradually retreated into private space. In Lebanon and the Middle East, however, the nativity scene remains vividly present in public life, serving not only as a religious symbol but also as a marker of history, geography, and identity.

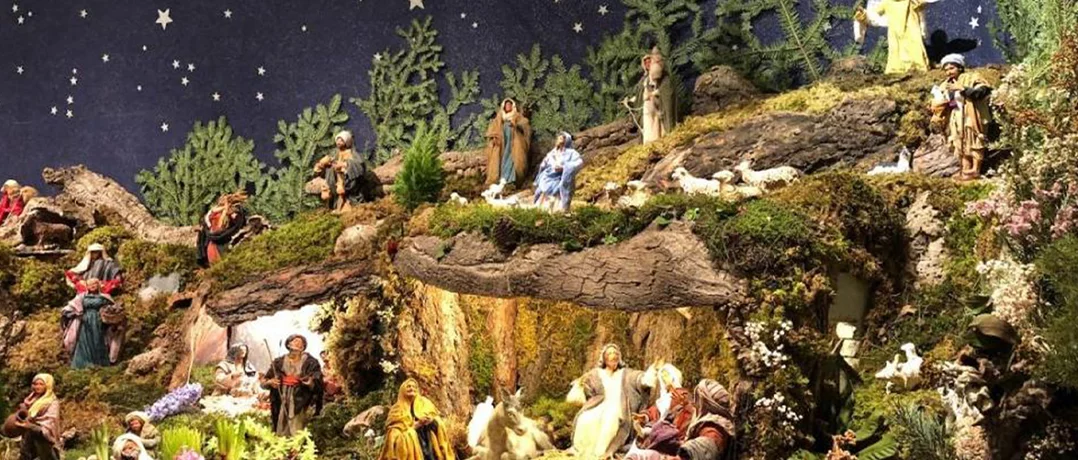

Launched by St. Francis of Assisi in 1223, a crèche is a traditional Christmas display, featuring Mary, Joseph, and the baby Jesus alongside a host of other characters, such as shepherds, wise men, angels, and a variety of stable animals.

While not exclusively Catholic, crèches are less popular among Protestant sects, which tend to be more cautious about religious imagery due to concerns about idolatry. As a result, the tradition became most deeply rooted in Catholic-majority societies, particularly in countries such as Spain, Italy, and France.

The crèche’s retreat in the West

Despite its Catholic origins, the crèche’s visibility in public life has declined throughout much of the Western. In the United States and many other Western countries, there is a concerted effort to keep religious practices private. While it is not unusual to find a crèche within the confines of a private home, rarely will such displays enter public spaces.

In France, for instance, home to the famously elaborate Provençal crèche, the nativity scene shifted from public spaces to private homes following the French Revolution, which banned public expressions of faith.

The United States reflects a similar dynamic, though shaped by institutional, rather than revolutionary, principles. With its constitutionally mandated separation of church and state, crèches have even become the subject of legal challenges. In 1984, when the city of Pawtucket, Rhode Island displayed a crèche as part of its annual Christmas display in a public park, the ACLU challenged this as a violation of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which bars government endorsement of a particular religion. The Supreme Court nevertheless rejected the claim, ruling that the crèche was permissible because it appeared alongside secular symbols such as Santa, reindeer, and a Christmas tree, and therefore did not amount to an endorsement of Christianity.

This ruling underscored a broader Western principle: the crèche may appear in public only when stripped of singular religious authority and embedded within a secular or pluralistic setting.

Lebanon and public Christianity

This Western retreat stands in sharp contrast to Lebanon. With one of the highest proportions of Christians in the Middle East, Lebanon possesses a long tradition of visibly integrating Christmas displays into public life. Crèches are among the most prominent expressions of this tradition and carry cultural, as well as religious, significance. Throughout the country, these displays appear in churches, malls, town squares, schools, restaurants, and private homes. They are often large and elaborate, and sometimes even serve as the centerpiece of a municipality’s Christmas decorations.

This visibility is inseparable from place. Middle Eastern Christians experience the nativity against the very landscape where Christianity began. The nativity story unfolds in Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nazareth, sites where many Middle Eastern Christians trace their roots back 2,000 years. The crèche is therefore not merely symbolic; it is geographic and historical memory and a reminder of their ancient roots in the region.

In regions marked by war, displacement, and political instability, the nativity story, in which Jesus is born amidst poverty and vulnerability, resonates deeply.

Lebanon’s religious diversity further shapes how the crèche is received. In Islam, Jesus (Isa) is a prominent prophet who is honoured for his miracles and divine teachings. While Muslims may not celebrate Christmas theologically, the figure of Jesus remains deeply respected. The crèche is therefore neither a visually threatening display nor a sectarian assertion.

This stands in contrast to Western legal frameworks, where religious symbols must be carefully balanced to justify their presence. The crèche can only be included in public spaces if it exists alongside secular symbols and those representing other religions, such as a menorah. On its own, the crèche is a religious display and holds no further cultural relevance.

Even the architecture of the crèche is distinctly Lebanese. The setting often mirrors traditional stone villages, with real moss used to evoke mountain greenery. Rather than a romanticized Western stable, the nativity is commonly depicted inside a cave, a setting rooted in Middle Eastern geography that anchors Jesus’ birth in a familiar, local landscape.

For Christians in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Jordan, the crèche is therefore not a seasonal ornament but a declaration of continuity: it is a link to the earliest Christians, a testament to ancestral roots, and a reminder of their enduring presence in this region.