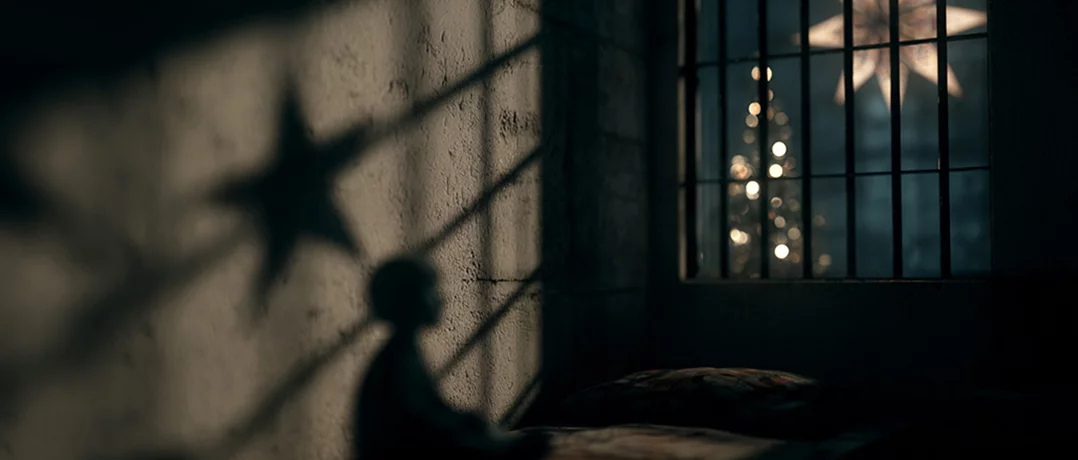

Behind festive celebrations, Lebanon’s detained children endure neglect and injustice within a juvenile justice system struggling to protect them.

Lebanon’s forgotten juveniles

While most children are celebrating Christmas with their families and friends freely, there are others in Lebanon thrown and neglected in devastating prisons and deprived of such joy, warmth and care. Although circumstances in life may have driven them to commit certain crimes, the Lebanese state has nevertheless aggravated their sufferings and enhanced the injustice that these children are facing. Indeed, for decades, Lebanon’s juvenile justice system has reflected the country’s broader institutional fragility: laws that promise protection, facilities that fail to deliver dignity, and procedures that too often turn vulnerability into lifelong marginalization.

Juvenile detainees have long been caught between punishment and neglect. While children aged 7 to 12 face particular and special measures, those aged 15 to 18 are subject to detention. Many may be detained for minor offenses linked to poverty, homelessness, or social breakdown, while others face more serious charges tied to organized crime or security-related cases. Until recently, all shared one reality: detention within a system designed for adults. These issues are also mentioned in various reports by Lebanese and international organizations, including ALEF – Act for Human Rights’ Monitoring Report (January-June 2025).

The transfer of juvenile detainees from Roumieh Prison to the newly inaugurated rehabilitation center in Warwar, Baabda, in May 2025 marked a historic shift. It was the culmination of more than 2 decades of planning and advocacy. Yet while the move represents meaningful progress, it has also exposed the deep structural contradictions of Lebanon’s approach to juvenile justice.

Life before Warwar: Juveniles in Roumieh prison

For years, minors in conflict with the law were held in Roumieh, Lebanon’s largest and most overcrowded prison. Although they were confined to a separate wing, their daily lives unfolded within a prison ecosystem entirely shaped by adult incarceration. Overcrowding, poor ventilation, limited access to outdoor space, and the absence of consistent educational or psychosocial programs defined their experience.

Detention conditions undermined the very principle of rehabilitation. Shared dormitories deprived children of privacy and security, while prolonged confinement enhanced anxiety, fear, and resentment. Contact with adult detainees, although formally restricted, was never fully preventable. In such an environment, pretrial detention (meant to be exceptional) became routine, even for minor offenses that would rarely justify incarceration in a functioning juvenile justice system.

A legal framework undermined by practice

Lebanon is not lacking in legal commitments to child protection. Law No. 422/2002, established a specialized regime for juveniles in conflict with the law. It prioritizes rehabilitation over punishment, mandates the involvement of social workers, provides for specialized juvenile judges, and emphasizes alternatives to detention such as supervision, educational placement, or community-based measures.

In practice, however, these safeguards are inconsistently applied. Pretrial detention remains the default response rather than the last resort. Specialized juvenile courts are unevenly staffed, and some cases involving minors have been handled by military or ordinary courts. Social services suffer from chronic underfunding, while mandatory training for judges, police officers, and lawyers remains limited or non-binding.

A particularly stark contradiction lies in the age of criminal responsibility, set at 7 years old (according to Article 3 of the Law No. 422/2002); well below international standards and inconsistent with the developmental realities of childhood. This low threshold continues to shape punitive practices that place children in detention rather than addressing the social conditions that lead them there.

Delays and their consequences

Systemic delays within Lebanon’s judicial system compound the harm experienced by detained minors. Many wait months, and sometimes over a year, before their cases are heard. These delays stem from a combination of factors: shortages of judges amid rising caseloads, judges’ strikes over salaries and living conditions, a lack of transport vehicles to bring detainees to court, and procedural rules that postpone hearings if any party is absent.

For minors, the psychological toll of uncertainty is severe. Detention becomes an indeterminate state, disconnected from any clear timeline or outcome. In some cases, children remain incarcerated longer than the maximum sentence their alleged offense would warrant. Such delays directly violate both domestic legal safeguards and international child rights principles.

The Warwar rehabilitation center: A long-awaited alternative

The opening of the Warwar rehabilitation center in May 2025 represented a long-overdue attempt to align practice with principle. Designed specifically for minors and built in line with international standards, the facility offers a stark contrast to Roumieh prison: bright, open spaces replace dark corridors, classrooms and vocational workshops replace idle confinement; and psychosocial support is integrated into daily life.

Funded by the European Union (EU) and supported by the United Nations (UN), the center can accommodate between 100 and 150 minors. It aims to function not as a prison, but as a rehabilitative environment where education, skills training, and psychological care prepare young detainees for reintegration into society.

For the first time, Lebanon has a facility that recognizes detained minors as children with developmental needs rather than as smaller versions of adult prisoners. This would aid in moving further away from a punitive approach towards a more constructive, sustainable and rehabilitative one, thus reintegrating these juveniles into Lebanese society in a healthy and productive manner.

Persistent gaps behind new walls

Despite its promise, Warwar has also revealed the limits of infrastructure-driven reform.

Shortly after the center opened, a tragic incident involving the death of a minor drew attention to ongoing shortcomings in psychological support, medical follow-up, and staffing. While the incident prompted investigations, it underscored a central truth: rehabilitation requires sustained human investment, not only modern buildings.

Staff shortages, inconsistent access to mental health professionals, logistical problems in meal provision, and delays in court transport continue to affect daily life inside the center. These gaps risk reproducing, in a new setting, some of the same harms that characterized juvenile detention in Roumieh.

Juvenile detention within a broader crisis

The challenges facing detained minors cannot be separated from Lebanon’s wider crises.

Armed violence, economic collapse, displacement, and institutional paralysis have increased children’s exposure to harm long before they enter the justice system. Monitoring reports from civil society organizations (such as the aforementioned one produced by ALEF) document persistent violence against children, neglect, exploitation, and discrimination.

Detention thus becomes not an isolated failure, but the final point in a chain of systemic neglect. Without coordinated policies addressing education, mental health, social protection, and community safety, the juvenile justice system will continue to absorb the consequences of broader state breakdown.

Beyond symbolic reform

The transfer of juvenile detainees from Roumieh to Warwar is a necessary and meaningful step. It signals a willingness, at least in principle, to move away from punitive confinement toward rehabilitation and reintegration. Yet symbolism alone cannot protect children’s rights.

Real reform requires raising the age of criminal responsibility, reducing reliance on pretrial detention, accelerating judicial procedures, and ensuring consistent access to legal, psychological, and social support. It also demands clear institutional accountability, adequate funding, and a national vision that treats child protection as a priority rather than an afterthought.

Warwar offers Lebanon an opportunity; not only to change where minors are detained, but to redefine why and how detention takes place. Whether that opportunity is seized will determine whether the country’s juvenile justice system becomes a path toward restoration or remains another cycle of loss for its most vulnerable children.