Reform on the clock

Reform on the clock

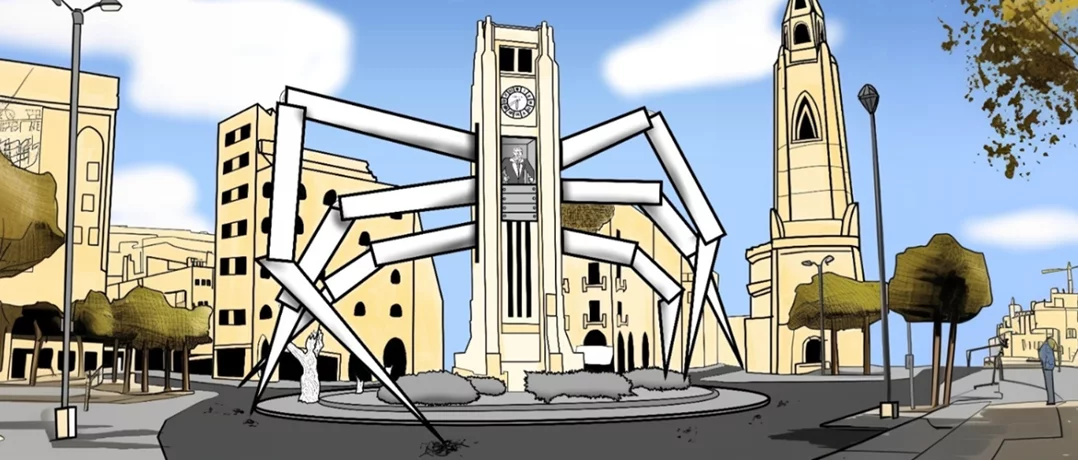

When Nawaf Salam, a judge heading the International Court of Justice, largely viewed as a reformer, was chosen to form Lebanon’s first government since the 2022 parliamentary elections, dozens of people gathered in Martyrs Square in central Beirut to sing, dance, and set off fireworks. To them, Salam’s appointment, along with Joseph Aoun being elected president less than a week prior, were signs of the dawn of a possible new Lebanon.

Months on, the fireworks have been extinguished, and the songs of hope are no more.

Both the new president and prime minister supported moderate and reformist politics that sought to bring the country out of the depths of the devastating economic crisis that started in 2019.

But reforms need time, and Salam, tasked with the burden of solving the country’s disastrous financial state, does not have the luxury of time. While Aoun will have until 2031 to work on the topics that he raised during his electoral speech in Parliament, Salam only has time to accomplish his goals until May 2026, when parliamentary elections are scheduled. Afterwards, his government will be forced into a caretaker status until a new cabinet is agreed on by all political factions.

It could take weeks, or it could take months, and a lot depends on the result of the ballot. Salam could continue with a new mandate, or he may not, analysts say. Theoretically, he still has less than a year to at least start some reforms, with many issues on the agenda, especially the economic and financial reforms, dragging already for almost nine months.

Parliament

Parliament

Economy deal, or no deal

When the economic crisis started in late 2019, few Lebanese could imagine the extent to which it would damage the country.

After being pegged at LBP 1,500 to $1 for over two decades, the Lebanese Lirax quickly depreciated, reaching an all-time low of LBP 111,000 to $1 in March 2023 before stabilizing at around LBP 90,000.

“The Lebanese people, business people, and consumers decided just to switch to dollars completely. To fully dollarize the economy,” Walid Marrouch, a professor of economics at Lebanese American University, told The Beiruter. “And then, the government was playing catch-up. So, it wasn’t really a government decision.”

After the crash of 2019, Lebanese banks locked depositors out of their savings, placing informal restrictions on how much people could withdraw each month.

In the six years of crisis, there have been continuous calls and discussions in Parliament about passing economic and banking reform laws that would allow for a restructuring of the system only for little actual progress to have been made.

Even when Lebanon reached a staff-level agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in April 2022, that was where reforms largely came to an end.

It was not until April 2025 that the Parliament finally passed a banking secrecy law, one of the changes demanded by the IMF to unlock a $3 billion loan from the global financier spread out over four years.

“I think many in Parliament, including [Parliamentary Speaker] Nabih Berri, are trying to kick the can down the road,” Paul Salem, vice president for international engagement at the Middle East Institute, stated.

Since the majority of current MPs are likely to get reelected next year and many of them want a deal, they will eventually come together to pass reforms that meet the IMF’s requirements so that international investment, aid, and reconstruction can begin, Salem pointed out.

At the end of July, Parliament passed a banking restructuring law, the second finance law needed as part of a long list of reforms, marking a monumental step in the nearly six years since the start of the economic crisis and was largely viewed as being a step in the right direction should it be implemented.

But even this may be little more than a symbolic gesture as parties might fight over the remaining financial gap law, potentially meaning that any money from the IMF could still be a long way off.

Photo by Mohamed Azakir, Reuters

Photo by Mohamed Azakir, Reuters

Regaining financial credibility

Even if there is no deal with the IMF, both Salem and Marrouch argued that it would not mean that Lebanon had no chance of pulling itself out of the crisis. Instead, it would just take the country longer.

Lebanon needs billions and billions of dollars to rebuild its economy. This cannot come from the IMF or the World Bank or from donors

“The IMF role is really to incentivize these government reforms for the government to do them,” Marrouch said.

According to Marrouch, the IMF loan is more about giving Lebanon a renewed sense of international credibility that would bring investors and their money into the country. In reality, the most important thing is that Lebanon passes these reforms that would allow the country to implement good oversight and governance so that Lebanon’s finances and economy are properly managed and future crises are avoided.

“It’s also a mentality that we need to go and beg for money [from international donors] but if you beg for money and don’t do the reforms, it’s like throwing coins into a pit that has no bottom,” Marrouch explained.

“You will waste these funds, and then you’ll have to go beg for more money. We have to put ourselves on a sustainable path where this economy can work for its people by having the right oversight and the right governance.”

In the end, however, international investors – most likely stemming from the Gulf Arab countries – would remain hesitant to bring their money to Lebanon and help fund the reconstruction of the country after the devastating war between Hezbollah and Israel as long as the Party of God remains armed.

“The Gulf countries and the international communities are not going to put major money in reconstruction as long as Hezbollah is armed and everything will be destroyed again,” Salem stated. “Similarly, Israel is unlikely to stop the barrages and attacks unless it is confident and the West is confident that Hezbollah is disarmed.”

.jpg) Young men hold posters during Ashura commemorations on July 6, 2025 stating "We will not leave the weapons." (Nicholas Frakes/The Beiruter)

Young men hold posters during Ashura commemorations on July 6, 2025 stating "We will not leave the weapons." (Nicholas Frakes/The Beiruter)

Facing a new Middle East

After Aoun was elected and Salam’s government gained confidence in Parliament, both of them made one thing abundantly clear: arms should belong to the state and the state alone.

This marked he first time that a president and prime minister, without directly saying it, called for Hezbollah to hand over its arsenal to the Lebanese State.

On top of that, with the country still in ruin from the war, the United States has informed Lebanese officials that no reconstruction aid would come until Hezbollah was disarmed.

Even prior to the war between Iran and Israel, this seemed like a long shot, although, for a while, Hezbollah did not explicitly say that it was unwilling to give up its weapons and expressed a limited level of openness to at least discussing the topic.

That came to an end during an April 18 speech by the party’s new secretary-general, Naim Kassem.

“We will not allow anyone to disarm Hezbollah or disarm the resistance, because Hezbollah and the resistance are one. The idea of disarmament must be removed from your heads,” Kassem stated defiantly.

While Iran, Hezbollah’s patron, gives the party a wide latitude when it comes to making decisions, disarming is something that would likely need approval from Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, himself.

“I think it’s quite clear that Iran and the Revolutionary Guards are not pressing Hezbollah to disarm,” Salem said. “After all, all the arms that they have are Iranian arms provided, paid for by Iran, so Iran’s say [is big] as to whether or not they give them up to the Lebanese state.”

There has also been a lack of support to disarm either Hezbollah or the Palestinian camps with there being no roadmap on how to do either of these things. Dates and deadlines have come and gone. However, in late August, members of Fatah in Burj al-Barajneh began handing their arms over to the Lebanese army, though other groups, such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad, have shown that they are less willing to do so.

“If you look at the Palestinian camps and how this has been clogged, basically, and thwarted. There’s no disarmament of Palestinian camps. That’s out of the window now,” Mohanad Hage Ali, the deputy director for research at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, told The Beiruter.

“[Hezbollah is] definitely facing an existential threat,” Hage Ali added. “If the regime [in Iran] collapses, they’re looking at a collapse themselves.”

This gives Hezbollah a vested interest, outside of the party’s core ideology of Wilayat al-Faqih, to ensure that there is no regime change in Iran.

Should Hezbollah wage a new conflict with Israel, it would almost assuredly mean further death and destruction for Lebanon.

“The gap is so huge with the Israelis that any confrontation with the Israelis would lead to a slaughterhouse in terms of land grabs, in terms of control and in terms of destruction and killing of what’s left of the organization’s membership,” Hage Ali stated.

But no matter how devastating another war would be, it would not necessarily mean Hezbollah’s disarmament but, according to Marrouch, it would ensure a negative economic impact on the country, which is currently heading in the right direction for economic growth, no matter how minimal.

At this point, Hage Ali explained, the only way that Hezbollah would disarm is if Aoun negotiated a new ceasefire agreement with the United States and Israel that would see Israel withdraw from the Lebanese territory that it currently occupies and give assurances that it would not launch any attacks on Lebanon so that the state could disarm the party.

On August 5 and 7, the government agreed to a U.S. proposal that would see Hezbollah disarmed and Israel cease its attacks and withdrawal from Lebanon. However, Hezbollah has completely refused to even discuss its disarmament as long as Israeli attacks continued and Israel occupied Lebanese territory. On the other side, Israel has refused to give any assurances that it would adhere to its end of the deal and would not lift a finger until Hezbollah was disarmed.

On top of these fundemental issues, as long as the regime in Iran stays in place, it would not want Hezbollah to disarm, so it would have at least some sort of threat to Israel next door, ensuring that the party would enjoy financial and military backing.

But as long as Hezbollah remains armed and a threat to Israel, Lebanon’s southern neighbor will continue to carry out strikes as it sees fit.

Even after the Lebanese army removed a majority of Hezbollah’s infrastructure south of the Litani River in the months since the November 27, 2024 ceasefire, Israel has continued to carry out drone and airstrikes on an almost daily basis.

“The law that we live in is a law in which Israel has the right to strike anywhere it wants at any point it wants,” Hage Ali said. “It’s a law that applies now from the Iranian-Pakistani borders to the Mediterranean Sea on Lebanon’s side. It’s a freedom of movement that’s basically a big title of Israeli hegemony in the region.”

This, Hage Ali added, was a new reality that Lebanon would “have to accept and live with” as any possibility for a renegotiated ceasefire that includes American and Israeli guarantees not being on the table for another year or two, well after the 2026 elections.