Siska’s "Still Water Runs Deep" reflects ports' histories of migration, trauma, and economic exploitation.

Still waters run deep: Beirut Art Center’s exploration into ports, power, and preservation

Still waters run deep: Beirut Art Center’s exploration into ports, power, and preservation

What do you envision when you conjure up a port? Ships? Goods? People? Movement? Perhaps you see them all. Perhaps different elements come to mind. Living in Beirut, perhaps you think “explosion.”

Beirut Art Center’s “Port Cities: Fragments of Maritime Routes” (October 9 - December 6) centers around the relationship between ports and the cities they shape. Originally a project by Liverpool Arab Arts Festival the exhibition gathered four artists from various port cities in a Liverpool residency to consider ports as both physical and figurative structures informing a city’s fabric. As a port city marked by a deep history with the slavetrade, Liverpool would serve as the launchpad before the exhibition traveled to the artists’ home cities of Tunis (Nadia Kaabe-Linke), Marrakech (Laila Hida), Cairo (Mohamed Abdulkarim), and Beirut (Siska).

Although ports have molded Lebanon’s identity since the ancient port of Byblos (3000 BC), their significance changed drastically following the 2020 port explosion. What form, then, would an exhibition centered around the implications of ports take in Beirut? And how would a Lebanese artist, one intimately familiar with ports’ volatility, approach such an endeavour?

To answer these questions, I met Siska for a tour of “Port Cities” the day after opening night.

Born and raised in Beirut, Siska left the city for Berlin in 2009. His relationship to his home city, however, remains complicated. Beirut, Siska explained, holds memories of trauma. Having come of age during the Lebanese Civil War, he describes his generation as one that endured “great loss and disillusionment.”

Such feelings prevented Siska from showcasing his work in Beirut for over ten years, even as he was invited several times and remained active abroad. “Port Cities” marks his first exhibition in Lebanon since leaving.

Why return now? “Port Cities,” Siska pointed out, does not focus on Lebanon specifically, but rather examines several cities’ legacies towards slavery, migration, and trade via ports. There is something easier in not speaking about Beirut explicitly. “The situation here,” Siska added, “can be too much to bear.” What Lebanon needs right now, he noted, isn’t criticism, but rather “care, support, and listening.”

Siska’s own connection to Beirut’s port is both personal and prophetic. Not only did his father work there during the final years of the Civil War, but Siska had filmed the nearby Electricité du Liban (EDL) building in 2011, unaware that nine years later the explosion would devastate the same area. Siska’s 2011 footage, originally intended as mere documentation, thus became witness to a future catastrophe.

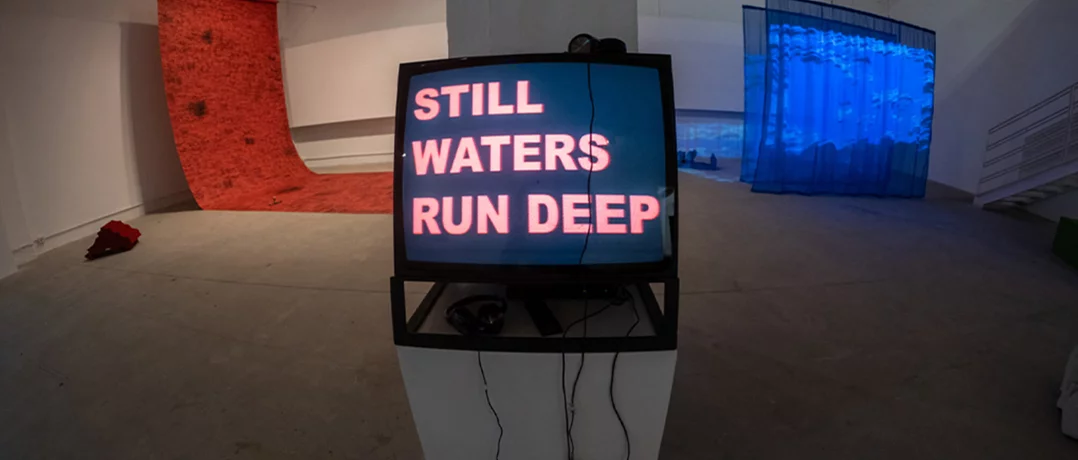

Although each artist created their own work for “Port Cities,” Siska’s contribution is a two-part piece titled “Still Water Runs Deep.” The first part features a massive piece of studio photography paper (2.72m x 11m) that lies partially on the floor, partially suspended in the air.

While the paper's layout remains constant, its background shifts by city; purple for Liverpool (the city’s colour), red in Marrakech (a nod to its nickname, “The Red City”), and red again in Beirut, both due to its inclusion in the Lebanese flag and the colour’s “alarming” nature.

One example of a proverb from the series reads:

Stamped across the paper surface reads a singular phrase, “Still Water Runs Deep.” While completing a residency at Villa Aurora in Los Angeles, Siska began compiling a lexicon of water-related proverbs that link the sea to themes of exile and migration for his stamp series cRY mE a riVeRs. One such proverb read:

“Those who drink the sea won’t choke on a river.”

يللّي بیشرب البحر ما بغصّ بالساقية

For this exhibition, Siska chose “Still Waters Run Deep,” as its familiarity in and around Liverpool tied it directly to the region where his six minute film, the second component of his piece, was shot. Considered alone, the proverb evokes hidden depths beneath a seemingly tranquil surface. Perhaps this obscured element is miraculous. Perhaps it is treacherous. The phrase allows for both interpretations.

Apply the proverb to Beirut and ports, however, and the meaning assumes a more sinister tone. The 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate which exploded in August 2020, while displayed in plain sight, proved to be far more lethal than originally imagined; as the blast revealed, Beirut’s port had been a ticking time bomb for years, seemingly waiting to blow up.

Upon the canvas, the phrase appears in both English and Arabic and is always horizontal. Several blurred blotches populate the paper marking whenever Siska repeatedly stamped within the same area.

Covering the entire canvas took approximately eight hours. By repeating the act of stamping, Siska hoped to draw parallels to the resurfacing of certain events throughout history and invoke the physical endurance of port labour. The stamped paper thus creates a new landscape, one of pressure, ink, and memory.

In Liverpool and Marrakech, Siska stamped alone. In Beirut, however, visitors joined him spontaneously, taking off their shoes to stamp beside him. Communal stamping had been the original concept of his piece. But when no one joined him at Liverpool, Siska abandoned the idea in Marrakech. For visitors on opening night unknowingly realize the original intention of the piece was “emotional” and “beautiful.”

Many English letters of the “Still Waters Run Deep” stamp are notably currency symbols: $ for S, £ and € for E, ₹ for R, ₦ for N, ₱ for P, ₺ for L. Highlighting the slavetrade’s monetary motives was a key intention of Siska’s piece. Staring down at the red paper, the currency symbols stare back at you ($₮I₺₺ ₩₳₸€₨ ₹U₦ D££₽), reminding viewers of the slavetrade’s economic foundations.

Why use a stamp rather than paint or text? There is a long relationship, Siska pointed out, between stamps (particularly visas) and power and bureaucracy. Ports, as places of entry and exit for migrants, bear witness to the implications of bureaucratic decisions. To hold a stamp in one's hand is to assume bureaucratic power. His stamping on a blank piece of paper therefore depicts what he chooses to do with such authority and represents a banalization of a previously decisive power.

“What monument would you expect beside a port?” he asked me during a lull in the conversation. I shrugged and confessed I had never given the question much thought.

In Liverpool, he continued, you would find the Beatles. In Hamburg, Otto von Bismarck stares boldly towards the water. Beirut, on the other hand, boasts its Lebanese Emigrant Statue. Created by Lebanese-Mexican artist Ramiz Barquet to commemorate early Lebanese migration, the cast bronze statue depicts a man dressed in traditional folkloric Lebanese outfit, gazing at the sea. من لبنان الى العالم (“From Lebanon to the World”) is graffitied across its base. Such monuments, port monuments if you will, communicate something critical about the identity a city wishes to project to its onlookers.

Siska rejects the idea of the Beatles as Liverpool’s defining port symbol. His film instead shows a monument near the Elbe honoring Admiral Nelson, beneath which four manacled prisoners sit with heads bowed. This, he argued, is the true monument in dialogue with the port. Liverpool might try to mask its slave trade legacy, he observed, but its reminders are in plain view.

What, then, defines a port? Port cities are centers of trade and commerce, yes, but they are also the first destinations for migrants who have fled poverty and conflict, seeking a better life.

A port, in its proximity to the inherent vastness of the sea, represents the unknown.

port is entry, a port is exit. A port of departure for some is simultaneously a port of arrival for others. Departure, however, can quickly turn to exile. Are these migrants leaving voluntarily? What forces drive them from the homeland?

A port is power. A port is authority. Who controls its access? What secrets and trauma does it contain?

Siska doesn’t have the answers, and neither do I. Yet to study ports, in all their contradictions, is to study a city and its history with an eye for all that is seen, submerged, and deliberately forgotten.

“Still waters run deep,” ends the film. How deep? Very deep.