The Beirut airport gambit

The Beirut airport gambit

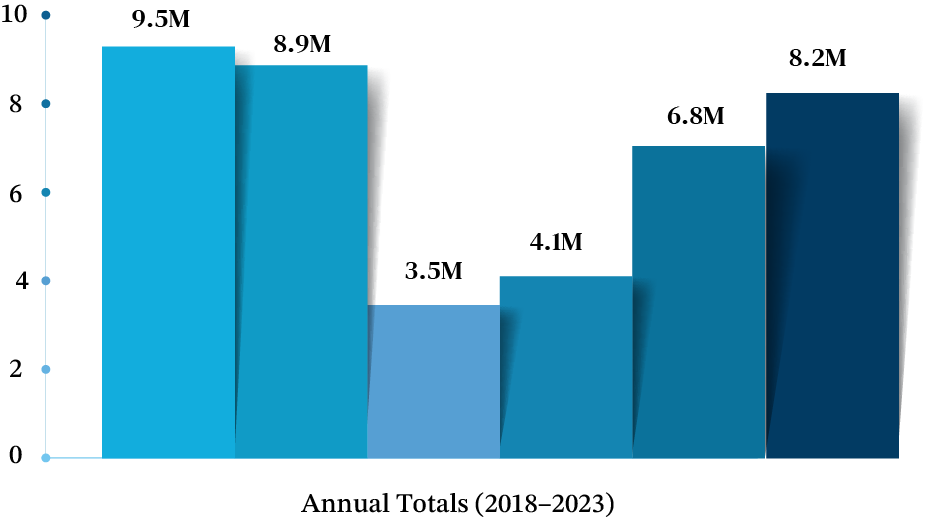

Transforming Rafik Hariri International Airport into “a world-class aviation hub” is a rather dated vision. However, the purported plan for Lebanon’s economic and social development includes public-private partnership (PPP) strategies for travel and tourism development, with two of these pillars specifically focused on aviation infrastructure. The first one is the construction of an additional terminal at Beirut airport, at present the country’s sole commercial aviation gateway. The second is a bet on elevating Rene Mouawad airport in Qlayaat, a dormant airfield between Tripoli and the Syrian border, and turning it into a functional airport by way of a PPP scheme. “With determination, innovation, and strategic partnerships, we will position our airport among the leading aviation gateways worldwide, reflecting Lebanon’s resilience, ambition, and unwavering pursuit of excellence,” Fayez Rasamny, Lebanon’s minister of public works and transportation, enthused, while inaugurating a smaller security-enhancement tech project at Beirut airport. In plainer terms, what both Rasamny said and Mohamed Hout, chairman of Middle East Airlines and de facto national aviation sector leader, echoed many times is that preparations for achieving the lofty aviation infrastructure ambitions have already been initiated. Independent from each other, they have confirmed in public appearances that both projects could take shape more concretely from early next year. One problem is money. While the aviation infrastructure projects have been presented, with entrepreneurial verve, as governmental development ambitions under the mid-term, they were not mentioned in either the very recent World Bank documents on the $250 million loan for war reconstruction or the International Monetary Fund’s press statement on the conclusion of a staff mission to Lebanon earlier in June. Another problem is time: the Beirut Rafik Hariri International Airport requires a comprehensive infrastructure upgrade that can enable it to operate as a 21st-century airport. A quick fix or an extra cheap terminal will not solve the shortcomings. Moreover, 21st-century aviation is a global transportation network of geostrategic importance that is exponentially more complex than 20th-century air travel. The world’s ten leading airports by annual passenger traffic, for example, have each recorded between almost 80 million and more than 100 million passenger movements in 2024, meaning that the passenger count at each of these airports was a multiple of all aviation users in 1960. Beirut passenger numbers officially released to date peaked in 2018 at 8.8 million. In 2023, a year of relative recovery, 7.1 million passengers were recorded, but this number again contracted significantly in the following year. In the first five months of 2025, passenger numbers increased by 5.2 percent year over year, reaching 2.41 million. It is indubitable that Lebanon has a sizable development deficit in its travel and tourism sector. The 2024 Travel and Tourism Development Index (TTDI), created by the World Economic Forum and the University of Surrey, ranks Lebanon 79th out of 119 countries. The low ranking reflects the country's struggles in building a strong, sustainable tourism. Although it must be noted that the 2024 TTDI is only the index’s second edition after 2021 and used a new methodology that bars direct historic comparisons, the WEF’s predecessor, Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI), ranked Lebanon some 15 years ago 70th out of 139 countries, at the halfway point of competitiveness. Keeping in mind the conflict-related disruptions and severe fluctuations of the past two years, as well as the impact of the global coronavirus aviation crisis and domestic economic meltdown of 2020-22, any assessment of travel and tourism in Lebanon indicates that the country’s comparative position in this sector has substantially degraded during the 2010s and the 2020s. Severe recent cargo aviation bottlenecks, impacting logistics and express shipping companies in 2024 due to the withdrawal of capacity and a quasi-monopoly over freight rates by national carrier MEA, suggest that the airfreight sector has not been exempt from degradation. Moreover, while somewhat stable in terms of absolute travel and tourism sector development, Lebanon’s regional position relative to its Arab neighbors has been eclipsed by progress in destinations and hubs such as the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Destination Beirut today also compares unfavorably to large and smaller Mediterranean hotspots such as Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and Malta. There seems to be very little that supports a vision of a rising aviation hub. Beirut presently does not serve as a logical intermediate point for travel to any major regional destination. Considering the shifts in passenger behavior, whereby demand for “point to point” direct flight links has reduced people’s acceptance of hopping from transit airport to transit airport under the ‘hub and spoke’ model of the 2000s, Beirut remains off most passengers' travel plans. To curb some enthusiasm…

A deep capacity deficit

The new paradigms

Shifts in passenger preferences over recent decades have not just been limited to growing appetites for straight journeys. Integration of smart ground transportation networks, simplification of security procedures, demand for quality services, and numerous other wants have influenced airport performance.

Meanwhile, the development of the Lebanese airport infrastructure was in the past 30 years has focused solely on the Beirut gateway. The location is extremely convenient for travelers, but at the same time, it abuts densely populated areas. This location not only has geographic limitations. It also faces economic questions over the optimal use of the land, a very scarce resource on the Lebanese coast.

Additionally, the location until very recently has been heavily infested with political issues and security concerns, a state that it has been in since the Lebanese Civil War. Throughout the 1990s post-conflict period and arguably until very recently, the ramping up of a unified national transport and tourism infrastructure was a dream that was consistently obstructed under local and regional power constellations.

Severe recent cargo aviation bottlenecks, impacting logistics and express shipping companies in 2024 due to the withdrawal of capacity and a quasi-monopoly over freight rates by national carrier MEA, suggest that the airfreight sector has not been exempt from degradation.

While announcements of a construction agenda for Terminal 2 at RHIA have been surfacing every few years in local media reports, more powerful agendas have played out in political rivalries, administrative paralysis, and clientelist cronyism, among many other economic and social distortions.

The internal Lebanese problems of broken infrastructure, a dearth of investment regulation, and economic corruption have not yet been overcome. They remain fatefully paired with longstanding geographic and demographic development barriers, as well as the contradictions of an asset-rich society but financially destitute state.

An upgrading and expansion of Lebanese aviation infrastructures, as well as ground transportation and related tourism infrastructure, will make excellent economic sense. But, externally and internally, barriers to becoming a tourism destination and travel hub cannot be talked away.

The country faces mounting pressures on all sides. Regionally, it struggles to compete with dynamic neighbors like the UAE and Saudi Arabia, whose strong performance in tourism and development highlights the growing gap.

At the same time, global challenges, from economic inequality and environmental threats to rapid technological change, add further strain, as noted in the TTDI report.

In this complex landscape, simply opting for the cheapest or quickest fix for RHIA’s new terminal would be a shortsighted approach, failing to serve Lebanon’s long-term needs or the visitors who cherish it.

Infographics by Joia Zbeidy, The Beiruter