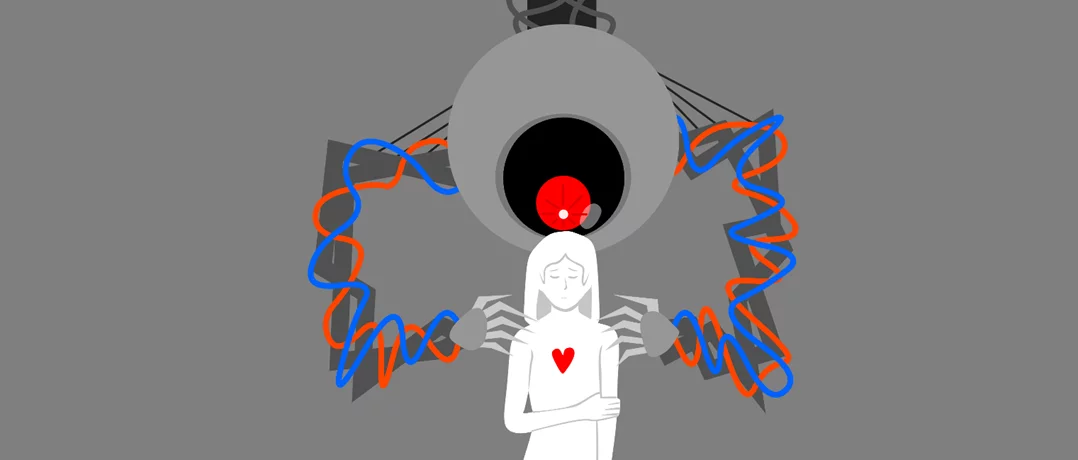

As millions seek emotional support from AI chatbots, experts warn that reliance on tools like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini raises serious ethical, psychological, and data privacy concerns.

The cost of digital comfort

The therapist has moved online.

Every day, millions of users type their fears, doubts, and personal questions into artificial intelligence platforms, seeking both information and reassurance. What began as a productivity software has evolved into something more intimate. AI tools such as ChatGPT, Claude and Gemini are increasingly acting as advisers, confidants and informal guides through personal uncertainty.

In an era marked by loneliness and growing public distrust, research has pointed to the role of social media in deepening isolation. A recent study published in the Journal of American College Health found that heavy social media use among college students was associated with significantly higher levels of reported loneliness, reinforcing concerns about digital connection replacing in-person interaction.

In that environment, AI’s appeal lies in its responsiveness. It answers instantly, never tires, and rarely judges. Its tone is calibrated to sound calm and tailored, the result of systems trained on vast datasets to detect patterns in human expression. For many, that combination feels safer than exposing vulnerability to another human being. But as reliance deepens, experts warn that emotional intimacy with machines carries cybersecurity risks that remain largely invisible to users.

Therapy without a therapist

The turn toward AI for emotional support is no longer fringe behavior. Experts at Columbia University’s Teachers College note that therapy and companionship have become among the most common uses of generative AI tools, underscoring how mainstream these systems have become in people’s emotional lives. But they caution that while chatbots may feel responsive and non-judgmental, they simulate empathy without genuine understanding, potentially reinforcing distorted thinking rather than challenging it.

Research from Brown University deepens those concerns. Through an evaluation of chatbot responses to clinical scenarios, the university found that large language models can fail to meet core mental health ethics standards, including by offering inappropriate reassurance or mishandling crisis scenarios.

Speaking to The Beiruter, cybersecurity and digital transformation consultant Roland Abi Najem said the psychological appeal is straightforward. “AI has a certain emotional intelligence,” he said. “It does not judge you. People feel more comfortable sharing sensitive thoughts with a machine.”

The data beneath the dialogue

What makes AI comforting is also what makes it powerful. Abi Najem said the shift toward emotional reliance on AI is unfolding faster than most institutions recognize, describing the technology as a system that thrives on intimacy.

“The fuel of AI is data,” he said. “The more we use these tools, the more we share insights about who we are and our fears, our medical conditions, our children, our beliefs. The system learns patterns about us.”

Every vulnerable disclosure becomes part of a broader data ecosystem. When users discuss their mental health or personal struggles, that information contributes to increasingly detailed behavioral profiles. AI systems analyze these patterns to refine responses and to better anticipate future ones.

Unlike a licensed therapist bound by professional confidentiality rules, conversations with AI platforms are not inherently private. Companies often store and analyze chat logs to improve services and may retain personally identifiable information as part of that process. Under legal orders such as warrants or subpoenas, companies can be compelled to disclose stored user data to authorities, meaning these interactions are not automatically shielded from law enforcement access.

Abi Najem argues that many users underestimate this reality and continue to confide in AI precisely because it feels private. “People trust these tools blindly,” he said. “There is very little awareness.”

Prediction and power

The implications extend beyond surveillance. AI systems are built to detect patterns. In medicine, that capability can predict disease years in advance. In seismology, it can anticipate earthquakes. Applied to language and behavior, the same principle allows models to infer mood, belief systems, and risk factors.

“Based on user behavior, AI can predict patterns such as whether someone may be at risk of suicide, or even about to commit a crime,” Abi Najem said. “It is all about collecting and analyzing data.”

Prediction carries both promise and peril. Early detection could enable intervention and support. But predictive profiling also raises the possibility of individuals being categorized or flagged based on an algorithmic inference, rather than action.

“There is a big error margin,” Abi Najem cautioned. “These models are predicting the next word based on data. They are not reasoning the way people think.” That distinction matters. While responses may appear authoritative, they are generated through statistical pattern prediction rather than human comprehension.

A new authority

When users turn to AI not only for facts but for moral framing and emotional and psychological support, technology begins to influence decision-making at a deeper level. As conversational systems grow more embedded in daily life, the question is no longer whether people will seek reassurance from machines. They already do. The more pressing issue is whether users fully understand the trade-off: emotional comfort in exchange for data and personalization in exchange for predictive insight.