The long Sunni winter

The long Sunni winter

The unrelenting summer sun beat down on the poster proclaiming unwavering support to Future Movement leader and former Prime Minister Saad Hariri. It hung on the side of a building in Tripoli, Lebanon’s second-largest city and arguably one of its most neglected, waving slightly when the reprieve from a brief breeze happened to blow through, its colors dulled and fading.

“A lot of the news around him is making it more clear that he will not come back to politics,” Obeida Takriti, a 34-year-old who ran on the Citizens in a State (MMFD) list in the 2022 elections, told The Beiruter. “No one is actually waiting for Saad Hariri. They are relying on local elites [to represent them].”

Hariri still enjoys fairly widespread support amongst Lebanon’s Sunnis, but, many have become resigned to the fact that, despite him announcing earlier in the year that he was going to return for the 2026 legislative elections, that was not guaranteed. After years without serious political representation, the community is also at a crossroads.

Throughout Lebanon’s history, many of the country’s Sunni-majority cities have fallen by the wayside and have been subjected to severe neglect.

This had little to do with the lack of political representation, but with the quality of representation. Development and investments were never delivered to the Sunni constituencies, former independent Tripoli MP Misbah Ahdab told The Beiruter.

On top of that, the region has seen monumental changes since the tail end of 2024, with Hezbollah, which arguably dominated Lebanese politics for well over a decade, being significantly weakened after its latest war with Israel and the fall of the Assad regime in Syria, which was replaced by a Sunni leadership in Ahmad al-Sharaa, who led the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

Because of these seismic shifts, Michael Young, a senior editor at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, said that Lebanon’s Sunni community was in a “transitional phase.”

People hold up posters of Future Movement leader Saad Hariri and his father, former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, and wave Future Movement flags in Martyrs Square on February 14, 2024. (Photo: Nicholas Frakes, The Beiruter)

Between pluralism and hegemons

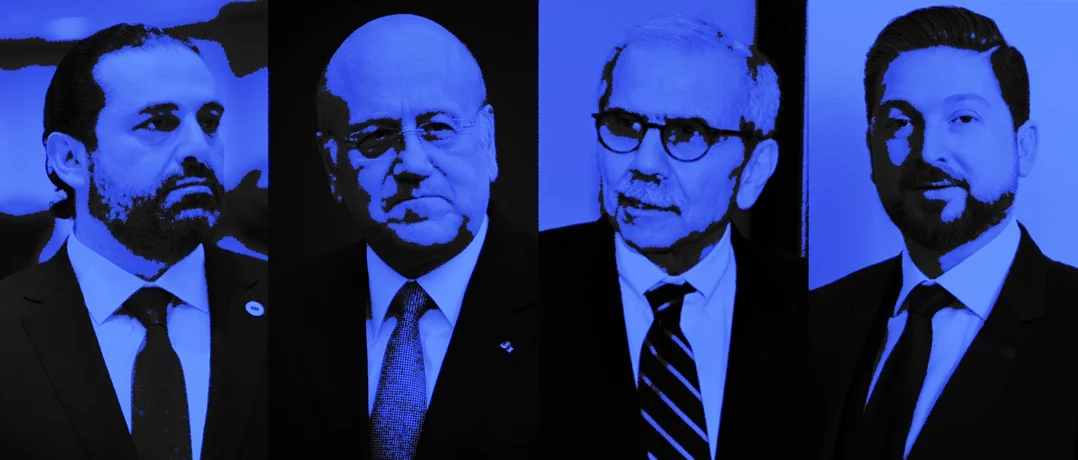

While the Hariri family and the Future Movement do continue to enjoy a certain level of broad support amongst Lebanon’s Sunnis, this largely has more to do with a lack of choices. Najib Mikati and his Azm Movement are usually able to win a handful of seats in the elections. Mikati, who has been prime minister several times, has been focused on running the country’s affairs rather than governing the community. Faysal Karami and his Dignity Movement are often less successful in elections. Karami himself barely made it to the Parliament in 2022. Other political factions backing various Sunni politicians in Tripoli have risen to fame and then vanished quickly from the political scene.

Before the rise of Rafik Hariri, Sunni politics unfolded similarly to those of the Maronite community. Multiple political families led the community, giving them a diverse list of electoral options. Some of these families included the Solhs and the Salams, with many of them serving as prime minister.

With the establishment of the National Pact by President Beshara el-Khoury and Prime Minister Riad el-Solh, power was divided in the country between Muslims and Christians – the Maronites getting the presidency, Sunnis the premiership and setting the sectarian quota in Parliament. In 1990, the Taif Agreement not only ended the civil war but formalized this pact. It was at this time that Hariri started to rise in Lebanese politics.

“The fact that Rafik al-Hariri was the dominant Sunni leader [for some time] was an anomaly. This was not the natural state of the community. The Sunnis supported him because he was a relatively powerful figure, and when he was assassinated, they all came out in support,” Young told The Beiruter.

When Saad succeeded Rafik after the assassination and the 2005 Cedar Revolution, much of his father’s support carried over to him. Future was one of the largest political factions in Lebanon’s Parliament, leading the anti-Syrian coalition March 14, often clashing with the pro-Syrian March 8, led by Hezbollah and the Free Patriotic Movement.

The fact that Rafik al-Hariri was the dominant Sunni leader [for some time] was an anomaly. This was not the natural state of the community. The Sunnis supported him because he was a relatively powerful figure, and when he was assassinated, they all came out in support.

In 2009, just four years after his father’s death, March 14 won the elections and Hariri became prime minister, but began facing challenges from the local Sunni leadership in the Bekaa Valley and north Lebanon, which largely stemmed from political and economic marginalization along with alliances with Hariri’s political rivals. The support for the Future Movement only continued to decline during the war in Syria. North Lebanon Future Movement politicians supported the Syrian Sunni uprising, but they could not compete financially and politically with the rise of a handful of politically active Salafist clerics who vocally spoke against Hezbollah interfering in the Syrian war alongside Bashar Al-Assad’s forces. The crowds filled their mosques, calling for a confrontation with Hezbollah.

Meanwhile, Hariri’s business empire started having financial hurdles, and the Future Movement failed to provide community aid as it had done during the 1990s and the 2000s. The decline continued after the November 2019 protests, when most Lebanese political parties confronted corruption accusations and criticism.

Hariri announced his return for the 2026 elections, but no real move to launch a campaign has been made yet. On the contrary, the comeback was rather hesitant. Weeks before the 2025 local elections, Hariri announced that Future Movement would not participate.

According to Young, it appeared that Hariri was still struggling to earn the backing of Saudi Arabia, which has long held significant weight in Lebanese politics. A lack of support from Riyadh may delay his return indefinitely.

Photo Ana Maria Luca, The Beiruter

Photo Ana Maria Luca, The Beiruter

Abdel Salam Musa, the general media coordinator for the Future Movement, told The Beiruter that Hariri had not yet made up his mind about returning to politics for the 2026 elections "based on the principle that 'everything in its own time is beautiful.'"

"The Future Movement will certainly abide by whatever decision Prime Minister Hariri makes and will remain under his leadership, as it has always been during critical junctures," Musa said.

A change in regional dynamics

While the Assad family held power, the regime in Damascus ensured that a strong Sunni leadership counter to its interests could not form either in Syria or Lebanon.

During the late 1970s, Syria invaded Lebanon to prevent Palestinian factions from gaining ground and avoid the Syrian military into direct conflict with Israel. At the same time, it gave them the ability to keep the Sunni community in check.

“This was in parallel with Syrian efforts to systematically ensure that the Sunni community remained pretty much under control,” Young explained. “Whenever there were signs of an independent Sunni voice emerging, for example, when [grad mufti] Hassan Khaled differed with the Syrian leadership, he was assassinated. So, any kind of Sunni leadership that could in any way threaten Syrian interests was liquidated.”

After 2024, with a Sunni Islamist government in power in Syria and a weakened Hezbollah, Lebanon’s Sunnis could make Lebanon’s Sunnis feel less suffocated. But an Islamist government in Syria might not have such a wide appeal to the urban Sunni population in Lebanon, especially after the history of the clashes in Sidon and Tripoli during the early years of the Syrian war.

“There will certainly be an Islamist appeal among some parts of the Sunni community,” Young stated. “I wouldn’t be surprised if you see Islamists-related groups or political figures emerging. We do have Salafi groups in Lebanon but they are by and large fairly weak and underfunded.”

Moreover, Sunni leaders who were seen as close to the Assad regime, especially Mikati and Karami, are likely to see losses in popularity.

There will certainly be an Islamist appeal among some parts of the Sunni community. I wouldn’t be surprised if you see Islamist-related groups or political figures emerging. We do have Salafi groups in Lebanon, but they are, by and large, fairly weak and underfunded.

Young said that, because outside of a possible return to a multi-polar Sunni political leadership, “candidates close to Hariri, the so-called moderate Sunnis, will do well.”

This is also a chance for local leaders of influential figures to make the move into politics, given the potential lack of involvement by the Future Movement in 2026 and the lack of a clear Sunni zaim (leader).

“A lot of the elites are looking at the election because the Future Movement isn’t participating in the upcoming election, directly at least,” Takriti said. “A lot of people want to use this opportunity to push themselves, the political elites in this case, and you can see a lot of people have started preparing themselves for the elections, especially in Tripoli.”

Given Tripoli’s significance as a Sunni-majority city and the second-largest city in Lebanon, politicians coming out of the city have a better chance of garnering influence and recognition on the national level rather than remaining stuck locally.

There is a concern about Sunni political disenfranchisement, Musa stated, but people cannot accept any Sunni marginalization, nor that of any other group.

However, former Tripoli Independent MP Misbah Ahdab argued that Lebanon’s Sunnis needed more than just a different type of political leadership: an agenda.

“What do we want? Where do we want to go? Rather than saying Mr. X is fantastic and he knows better for us what should be done,” Ahdab told The Beiruter. “These things need to be black on white; it has to be clear. We’re at a crossroads now to see what kind of country we’re going to put together.”

Lebanese Sunnis, Ahdab explained, are not seeking to have a Sunni state or Sunni enclaves in the country. Rather, they are seeking “to be in Lebanon, but a Lebanon in which we are included, not in which we are persecuted and excluded from any development or any representation.”