Venezuela and Saudi Arabia hold the world’s largest oil reserves, yet their contrasting production levels show why resources alone no longer guarantee power or prosperity.

Venezuela vs. other petro-states: The paradox of oil wealth

Venezuela vs. other petro-states: The paradox of oil wealth

Oil has long shaped global politics, economies, and power structures. But in the modern energy landscape, having the most oil in the ground no longer guarantees economic clout, prosperity, or geopolitical dominance. Nowhere is this more evident than in the contrasting stories of Venezuela and Saudi Arabia, two countries near the top of the list of global oil reserve holders, yet with vastly different outcomes.

A world charted by Black Gold

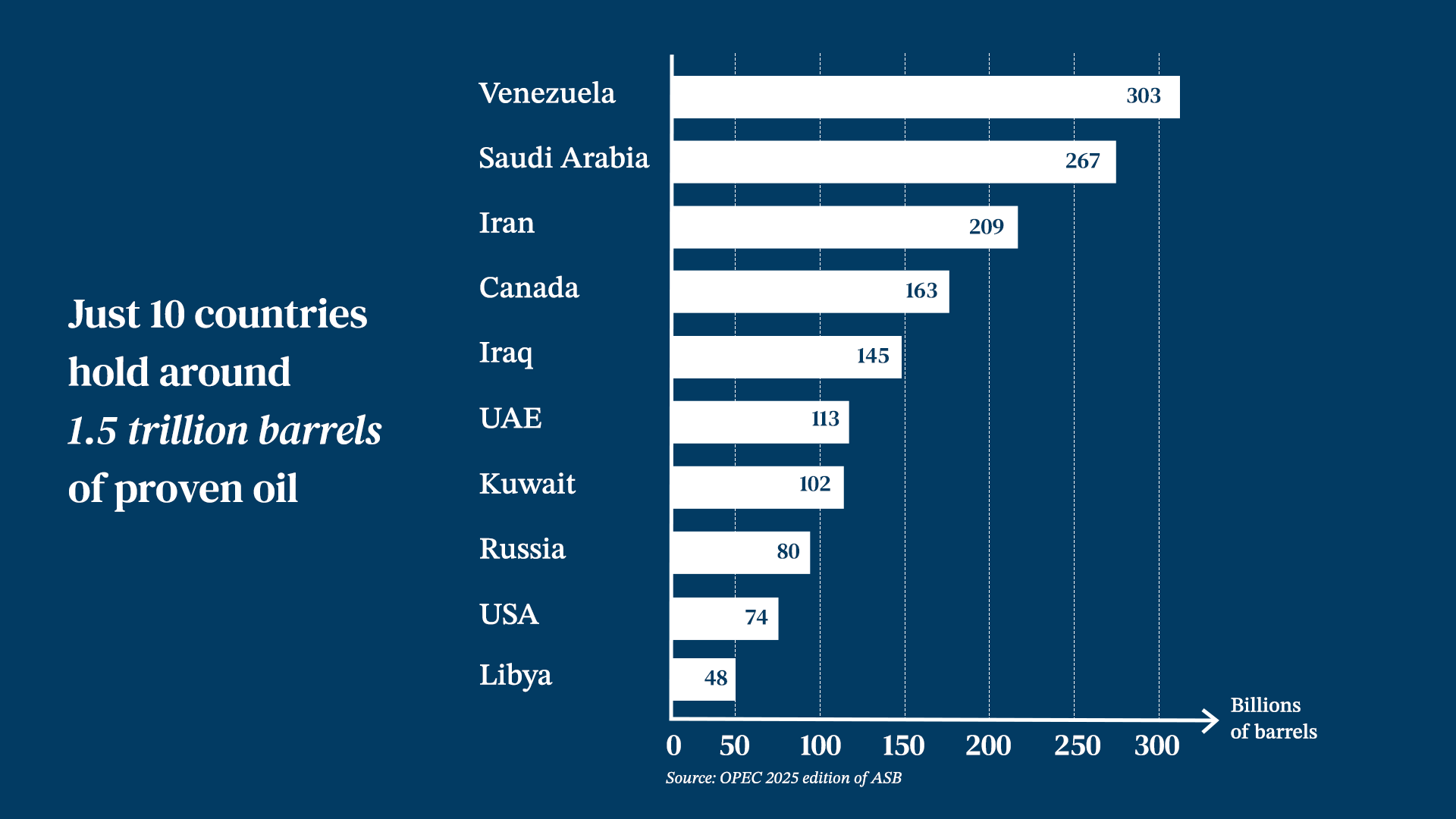

According to the OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin 2025, just ten countries hold roughly 1.5 trillion barrels of proven oil reserves.

Source: OPEC 2025 Annual Statistical Bulletin; global energy rankings

On paper, Venezuela sits atop the world. Its 303 billion barrels of proven reserves represent roughly 17 – 20 percent of all known oil reserves, more than any other nation. Most of that oil lies in the vast Orinoco Belt, a region rich with extra-heavy crude that could fuel global energy markets if fully exploited.

But there’s a catch: oil in the ground and oil flowing into markets are very different things.

The Venezuelan paradox: Most oil, least output

Despite its astounding resource base, Venezuela has fallen far behind in actual production. At its peak in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the country produced over 3.4 million barrels per day, ranking among the world’s top producers. Today, output has collapsed to under 1 million barrels per day, accounting for less than 1 percent of global supply.

There are several reasons for this stark underperformance:

Heavy crude challenges: Most of Venezuela’s oil is extra-heavy and highly viscous, requiring blending or specialized refining to make it transportable and marketable, an expensive and technically demanding process.

Aging infrastructure: Decades of underinvestment, neglect, and declining maintenance have left pipelines, wells, and refineries in disrepair.

Political instability and sanctions: Long-standing U.S. sanctions on the state oil company PDVSA, political turmoil, and loss of skilled labor have crippled industry operations.

Saudi Arabia offers a stark counterpoint. From the moment oil was struck at Dammam Well No. 7 in 1938, the kingdom embedded hydrocarbons into a long-term state-building strategy. That discovery, later known as the Prosperity Well, laid the groundwork for Saudi Aramco, now the world’s largest oil company by production and one of the most valuable firms globally. Today, Saudi output hovers around 10 million barrels per day, close to 10 percent of global supply, granting Riyadh exceptional leverage over oil prices, supply management, and energy geopolitics.

Saudi Arabia does not stand alone. The wider Gulf region remains the backbone of global oil markets. Collectively, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries hold around one-third of the world’s proven oil reserves and command a substantial share of global production capacity. The United Arab Emirates accounts for more than 5 percent of global reserves, while Kuwait, home to the giant Burgan field, holds roughly 6 percent. Iraq, another pivotal OPEC producer, ranks among the world’s top reserve holders, with the Rumaila field alone producing over 1.5 million barrels per day.

Crucially, Gulf producers also control much of the world’s spare production capacity, oil output that can be rapidly activated during supply disruptions. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Iraq together hold several million barrels per day of this buffer capacity, giving them unmatched influence over market stability during geopolitical shocks, sanctions, or global demand surges. This flexibility extends their power far beyond export volumes, turning oil into a strategic tool rather than a simple commodity.

As the global energy system evolves under technological change, climate pressures, and geopolitical fragmentation, the contrast between oil-rich states becomes increasingly clear. Reserves alone do not confer power. What ultimately determines a country’s standing is how effectively those reserves are governed, financed, produced, and integrated into global markets.

The broader lesson is unmistakable: geological wealth is a starting point, not a guarantee. Nations that combine resource endowment with stable institutions, credible policymaking, sustained investment, and technological capacity can translate oil into long-term influence and economic resilience. Those that cannot risk seeing even the largest reserves remain stranded, rich beneath the ground, yet marginal above it.