Promised as a solution, Lebanon’s Financial Gap Law risks repeating history, shifting losses onto depositors through delays, bonds, and uncertainty.

We’ve been here before

The so-called Financial Gap Law, which is still to be ratified, will allow the Lebanese to access money frozen after the spectacular collapse of the banking sector in October, 2019.

But nothing is straightforward in Lebanon. Depositors are unhappy with the ‘conditions’, which promise the first $100,000 over four years in ‘cash’, and the rest, should however little, in the form of a government-backed bond that matures in either 10, 15 or 20 years depending on how much is in the frozen account. The bonds can be sold before maturity, but any buyers will surely demand a hefty discount.

The main bone of contention is that 84% of depositors have less than $100,000 and represent a mere 18% of the frozen deposits. Surely, depositors argue, it is this tranche that should be prioritised and get their money immediately. Many are elderly and need to make provisions before it’s too late.

The bonds earmarked for the 16% of depositors who have over $100,000 will be underwritten by Banque du Liban, which, apart from its $40 billion in gold reserves, also has stakes in Casino du Liban, Middle East Airlines, swathes of land across the country and the Intra Investment Company.

The latter is well known to Lebanese of a certain age, business journalists, historians and conspiracy theorists. Created in 1970, the Intra Investment Company’s main assets include Casino du Liban, extensive real estate holdings across the country and financial institutions such as Finance Bank.

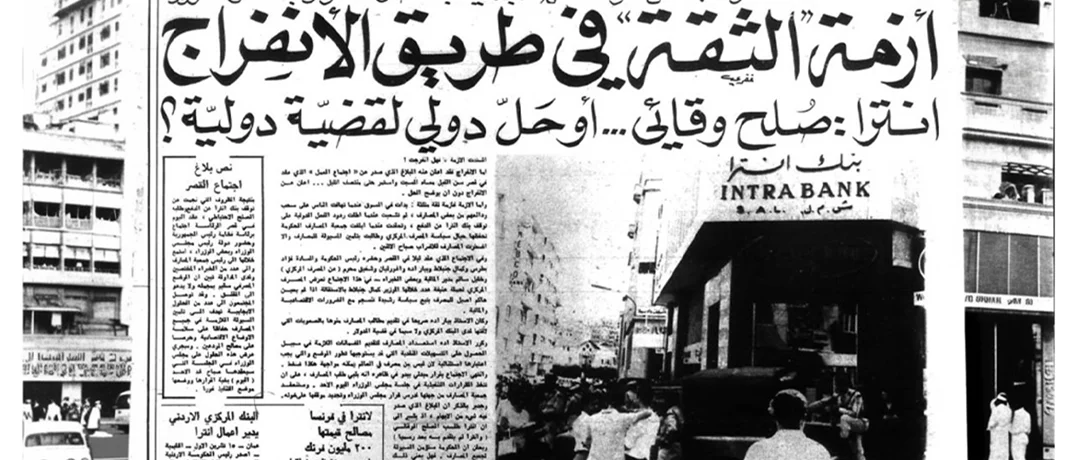

It is yet another Lebanese construct, a phoenix that rose from the ashes of Intra Bank, at the time the biggest financial institution in the region and one that captured Lebanon’s so-called golden age.

Intra Bank’s collapse 60 years ago was the largest financial scandal in the Middle East and brought another generation of Lebanese depositors to their knees. Back then, those who lost their money were given shares in the Intra Investment Company, which has been shrouded in controversy ever since.

The Intra Bank saga is a cautionary tale. Founded by brilliant Palestinian banker Youssef Beidas and three other investors in 1951, by the early-1960s, it had offices in the United States, major European capitals, Brazil, the Bahamas, and West Africa. Assets included serious real estate in New York and Paris, Lebanon’s national carrier Middle East Airlines, and a major French shipyard.

But Beidas’ power eventually wore down the patience of a Lebanese establishment that saw him as an upstart, arrogant and indiscreet (especially after a few drinks) and one that meddled in politics, a mistake for a ‘foreigner’, even one who held regional influence. In short, Beidas, a man with so much of Lebanon in his pocket was, seen as a threat and had to go. And so, in 1966, in a fit of xenophobic pique, the Lebanese authorities helped engineer the Intra’s collapse.

His fall was swift and brutal. In early October 1966, it was leaked that Intra was in difficulty. The rumours allegedly came from the presidential palace and the office of the prime minister, and then from Intra rivals. There was a run on the bank. Depositors rushed to retrieve their money and Banque du Liban, which should have intervened, did nothing, even when it was bailing out other local banks caught up in the panic.

The late publisher and businessman, Naim Attalah, himself Palestinian and who worked closely with Beidas, had this to say when I interviewed him in London in 2006. “The whole affair showed an inherent corruption and vindictiveness in our society and Beidas was the victim. When there is a run on a bank in every civilized economy in the world, the central bank comes to its aid. It quashes rumours and tries to stop it. In the case of Intra, it did nothing [and in doing so] it destroyed the financial credibility of Lebanon. I don’t think the country has recovered since.”

In his autobiography, The Flying Sheikh, Najib Alamuddin, the late MEA chairman and government minister, called the Intra affair “the beginning of the disintegration of Lebanon [by] a system … corrupt in style and morals that had plagued Lebanon since independence and finally plunged the nation into civil war.”

Yes, the Financial Gap Law needs reviewing, but the bigger question is whether or not the country has learned from its mistakes.