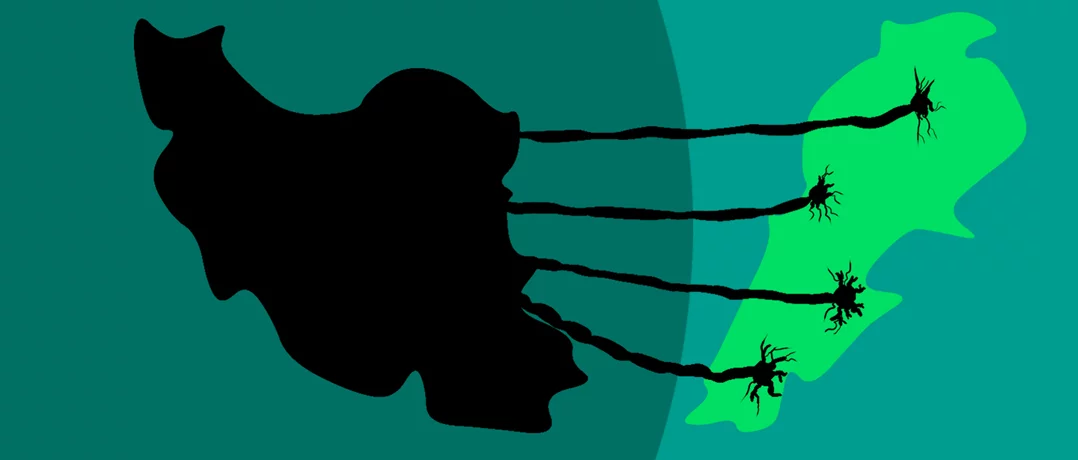

A deep look at how Iran filled the void left by Imam Musa Al-Sadr to reshape Lebanon’s Shiite community and extend its influence across the country’s political landscape.

From absence to dominance: Iran’s long road into Lebanon’s Shiite sphere

From absence to dominance: Iran’s long road into Lebanon’s Shiite sphere

Over the span of decades, Iran’s clerical regime succeeded in tightening its grip over Lebanon’s Shiite community, binding it to Tehran’s strategic interests to the point that Lebanese national priorities have become almost entirely absent from the agenda of the forces claiming to represent that community. This influence did not stop at internal Shiite decision-making; it gradually extended to the broader Lebanese political landscape, in a process shaped by overlapping factors and unfolding through multiple stages.

The disappearance of Imam Musa Al-Sadr stands out as one of the most pivotal turning points that paved the way for this project. His absence he being the unifying national reference for the Shiites created a vacuum that Iran was quick to fill, presenting itself as the new spiritual and political patron. Later came the conflict between Hezbollah and the Amal Movement, which solidified a new reality that ultimately entrenched Iranian influence both on the ground and within the Shiite equation, laying the foundation for Tehran’s deeper penetration into Lebanese national decision-making as a whole.

Imam Musa Al-Sadr was far from an ordinary figure in the history of the Shiite community or in the Lebanese political equation. His presence marked a turning point in the trajectory of the Shiites in Lebanon. Through structured, deliberate engagement with the pre-war Lebanese state often described as the era of “Political Maronitism” he established the first formal institutional framework for the Shiite community: the Supreme Islamic Shiite Council. This was more than an administrative milestone; it was a declaration of a distinctly Lebanese Shiite authority, one that anchored the community’s national belonging and granted it an independent institutional voice within the political system.

Imam Al-Sadr grounded his approach in Lebanese national interests, placing Lebanon’s priorities above ideological or cross-border agendas. This stance profoundly reinforced the Shiites’ final and irreversible attachment to Lebanon. In this spirit, he opposed transforming South Lebanon into a staging ground for Palestinian guerrilla operations, warning that such actions would cause Lebanon to lose its own stability without regaining a single inch of Palestine. “We will become refugees if we do not keep Lebanon neutral,” he cautioned, stressing that the country, with its limited capabilities, could not bear the weight of the Palestinian–Israeli conflict.

This approach placed him squarely in the path of regional ambitions. Hafez Al-Assad, intent on subjugating Lebanon to Syrian influence and deepening internal divisions, viewed Al-Sadr as a formidable obstacle. It was not easy for Assad to accept a Shiite leader who insisted on a distinctly Lebanese identity for his community and rejected the logic of civil war especially given the sectarian affinity between Shiites and Alawites that Al-Assad sought to exploit.

Thus, actors as diverse and often antagonistic as Damascus and the Palestine Liberation Organization found common cause in silencing Imam Al-Sadr. His removal would pave the way for reshaping the Shiite community’s political orientation according to external calculations and steering it toward agendas far removed from Lebanese interests. Indeed, the aftermath proved this: first, the Shiites were drawn into Yasser Arafat’s orbit through leftist parties, and later they fell under Syrian tutelage through the Amal Movement.

The Islamic Revolution in Iran then redrew the landscape once more. After taking power, Ayatollah Khomeini set his sights on the Shiites of Iraq and Lebanon. He launched a devastating war against Iraq from which he emerged weakened, describing his acceptance of the cease-fire as “drinking poison.” In Lebanon, Tehran dispatched Revolutionary Guard commanders to train armed cells and build a political nucleus loyal to Iran. These groups would eventually evolve into Hezbollah, which formally announced itself in the 1985 “Open Letter to the Oppressed,” declaring its aim to establish an Islamic order in Lebanon bound to the authority of the Supreme Leader.

From the outset of its regional expansion, Iran’s primary objective was to consolidate its influence within the Shiite community and use it as an entry point to shape Lebanese decision-making. This explains Hezbollah’s trajectory during the Lebanese civil war: the party refrained from engaging militarily with any Lebanese faction except the Amal Movement.

That conflict between “members of the same household” was neither incidental nor spontaneous it was part of a calculated strategy. Through it, Tehran succeeded in securing Hezbollah’s dominance over Shiite areas at Amal’s expense.

This process enabled Iran to tighten its grip over the Shiite political sphere and, through it, expand its influence throughout Lebanon. The arrangement eventually reached a Syrian-Iranian equilibrium: Amal would represent the Shiites within the political system managed by Hafez al-Assad, while Hezbollah would retain exclusive military authority under the banner of “resistance.” With time, both Amal and the Assad regime itself fell under Iranian sway, allowing Tehran to consolidate unprecedented control over Lebanese political decision-making.

It is true that Muammar Gaddafi bears direct responsibility for the abduction and disappearance of Imam Musa Al-Sadr, and equally true that both Yasser Arafat and Hafez Al-Assad had clear interests in his elimination. Yet what stands out is the position of post-revolution Iran. Despite Al-Sadr’s stature as a leading Shiite cleric, Tehran maintained cordial relations with Gaddafi’s regime and never adopted a firm or confrontational stance toward Libya over the case. This Iranian silence raises serious questions about the regime’s own interests in Al-Sadr’s disappearance.

This leads us to the natural question:

Would Iran have succeeded in its project to dominate Lebanon’s Shiite community and gradually detach it from its Lebanese identity had Imam Musa Al-Sadr remained alive and present on the national stage?

For many, the answer is a resounding no. With his charismatic presence, national vision, and unique ability to balance social, political, and spiritual leadership, Sadr represented a formidable barrier to any attempt to align the Shiites with external axes. He had the credibility and authority to safeguard the community’s independence, reinforce its Lebanese identity, and shield it from being instrumentalized in regional power struggles.

In other words, the disappearance of Imam Musa Al-Sadr did not merely create a leadership vacuum it opened the door for the Iranian project that would go on to reshape both the Shiite community and Lebanon itself.

For decades, the Mullah regime in Tehran has succeeded in tightening its grip on Lebanon’s Shiite community and binding it to its own strategic interests. This influence has grown to such an extent that Lebanese national interests have become nearly absent from the political orientations of the forces claiming to represent the community namely Hezbollah and the Amal Movement.

The regime’s control did not stop at dominating decision-making within the sect; it expanded to encompass Lebanon’s broader political sphere. This came as the result of a long trajectory marked by intertwined factors and successive stages from the power of arms and systematic intimidation to political assassinations targeting its opponents. This trajectory culminated on May 7, 2008, a turning point that placed Lebanon entirely under the sway of Iran and Hezbollah.

In conclusion, Lebanon under Iranian influence has eroded many of the defining features of Shiite identity an identity historically known for its intellectual openness, rich diversity, and traditions of dialogue and engagement with others. Lebanon itself has also been pushed into contradiction with the very idea of its founding: a nation built on partnership rather than exclusion, on freedom rather than coercion, and on openness to the world rather than retreat from it.

Restoring this essence is not merely a cultural or political choice; it is a necessity so that the Shiites may reclaim their heritage, and Lebanon may return to the values on which it was founded and to a constructive role within its Arab surroundings and the international community.